![]()

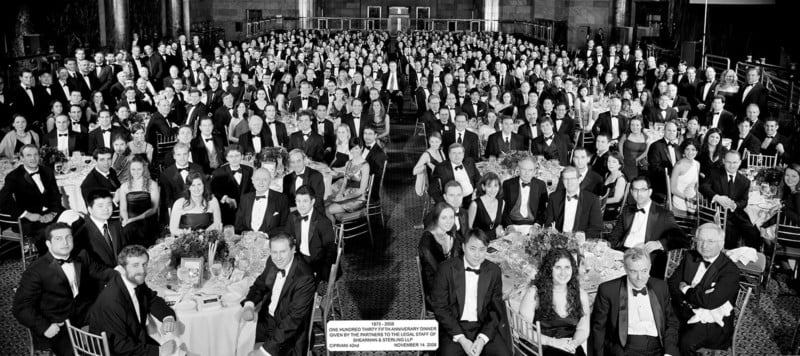

Terry Gruber is probably one of the last portrait photographers in the United States to still use a 100-year-old, 12×20-inch banquet camera for its original purpose: capturing large groups in formal occasions.

What is a Banquet Camera?

A banquet camera is similar to a view camera that holds an extra-long 12×20 inch film back. They were also made in 7×17 inches. The most significant advantage of the banquet camera was that a contact print of 12×20 was large enough for framing, and it showed every face of the 150 to 500 people in the group to be recognizable and even tack sharp.

Banquet camera photography was popular from the late 1880s until the late 1960s, when it began to fade away.

The resolution of a banquet photo has had some interesting uses over the years — the final photo in The Shining is a banquet photo where they zoom into Jack Nicholson’s face.

“Yes. That was a real banquet photo where Jack Nicolson was retouched into it,” Gruber tells PetaPixel.

$3,500 Per Banquet Photo

Gruber charges $3,500 per banquet photo, and if you think that is pricey, you may change your mind once you learn of all the time, effort, and stress that goes into making a single photo.

“We arrive at least 3 hours before the photo is taken,” Gruber says, “Three of us.

“One shot Terry they say. It’s a one-shot deal unless you’re outside without flashbulbs.”

A modern photographer must shoot many frames to find one where no one has blinked in a large group. With this unusual type of portrait, however, one is enough.

“Jayson [his mentor] explained that in the 1-second exposure lit by the bulbs, people may blink, but their eyes are open longer than the blink,” he says. “We almost never have a blink.”

The Camera and Operation

Gruber uses a Folmer and Schwing banquet camera made in or around the year 1920. The company was founded in 1887 by William F. Folmer and William E. Schwing as a bicycle company in New York City. The first cameras appeared in their catalog in 1896. Mr. Folmer developed the first Graflex camera in 1898. From 1905 to 1926, the company was a division of Eastman Kodak in Rochester, New York.

The banquet camera came with one back, and Gruber had two more custom-made. The camera weighs 20 pounds (~9kg) and the tripod is 15lbs (6.8kg) The entire kit including the lighting for the shoot is over 100lbs (~45kg).

“For an indoor shot, I have a 14-inch (~350mm) and 16-inch (~400mm) threaded lens with a Packard shutter with a lemon which is an air squeeze black bulb [for keeping the shutter open],” says the banquet photographer. “For an outdoor shot with flashbulbs for fill light, I use a lens with a shutter — a 14-inch Goerz Dagor with a Copal shutter.

“The reason for this is the movement of people at ½ or one second is about all the shot can take, and a Packard shutter [squeeze bulb] is harder to keep open for less than a second.

“The last time I calculated [angle of view] that, I believe, we measured 61 degrees which would be equivalent to 26mm in 35mm format.”

A normal lens is the size of the diagonal of the film and, in this case, would be about 600mm.

“If you cannot see the camera, the camera cannot see you,” is what Gruber shouts when shooting a big group. And to help the camera see everybody in these humongous groups, the camera must be very high.

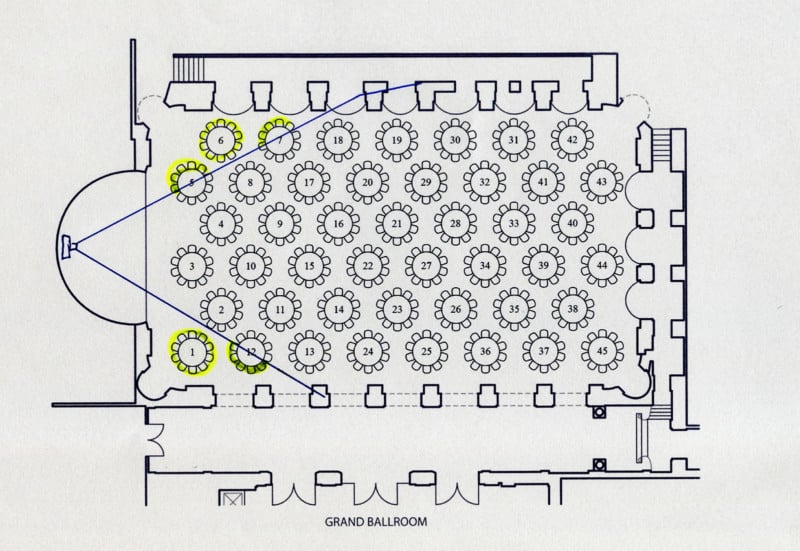

Gruber mounts the camera on a 9-foot collapsible wooden tripod and climbs onto a 10-foot ladder to frame, focus, and shoot. The framing and focusing are actually done on a focusing chart — his mentor used a candle flame — before the people enter the room.

Gruber says that many good banquet photos are taken from a balcony 25 to 30 feet up. Large centerpieces must be removed from the table to avoid people being hidden behind them, which can be a little troublesome for the event planners.

Lighting a Crowd with Flash Bulbs

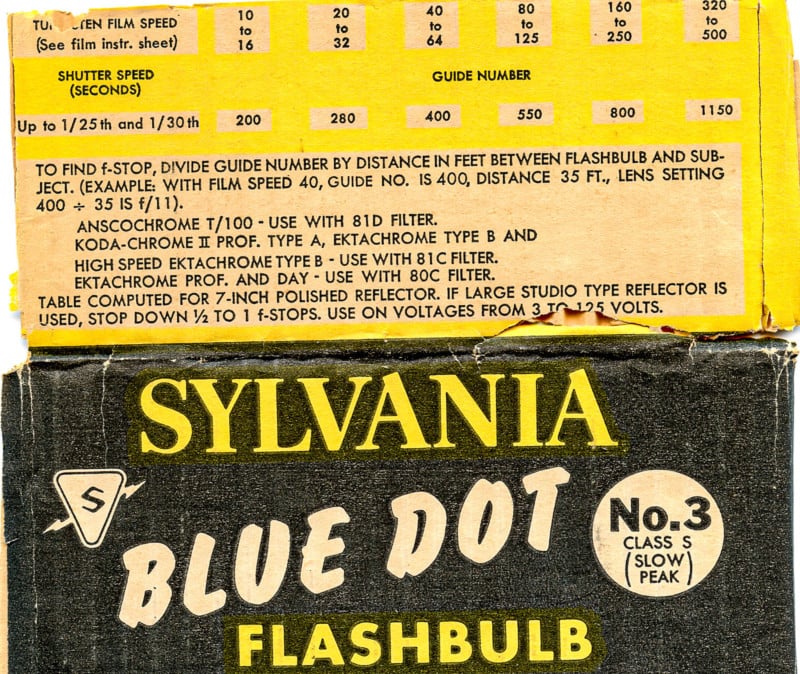

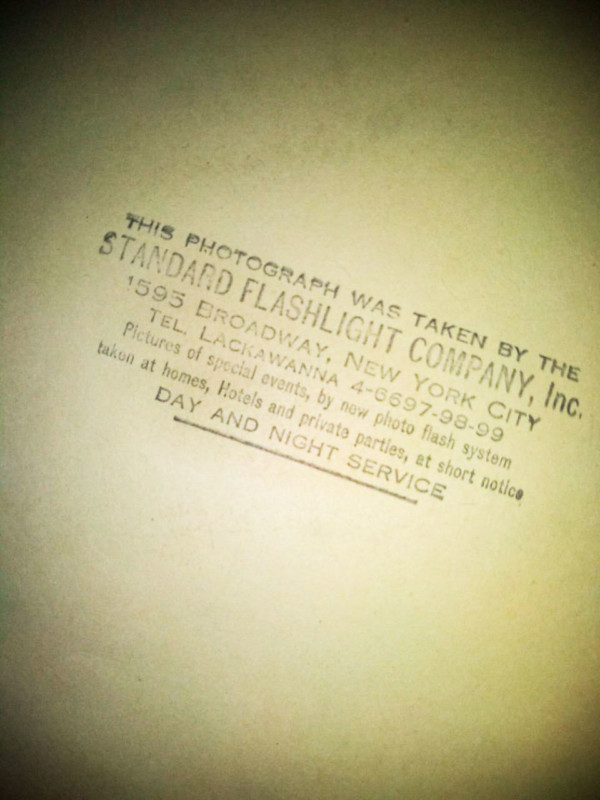

Most banquets are indoors, and the lighting for Gruber is still flash bulbs (first produced by GE in 1927) to get the authentic look of a banquet photo. Flash bulbs are very bright and emit a lot of heat, and the momentary brightness of the flash can be startling to the audience.

“You can actually feel a wave of heat when you have fired multiple bulbs,” says the banquet photographer. “I buy them off eBay. I have enough in storage to shoot 50 banquets.

![]()

“[I] never [use] constant light or strobe. An average shot with 200 people is 8-9 flashbulbs. A big space like the Koch Theater at Lincoln Center in New York took 16 bulbs and 350 feet of wiring. I use the Sylvania #3 clear for black and white.”

In the days before flashbulbs, flash powder (magnesium, etc.) was used, which provided a bright light but was very dangerous, especially in closed ballrooms. According to Gruber, there were contraptions that would catch the dense cloud of white smoke in canvas bags when they exploded the flash powder. And then, the assistant would carry the bag of smoke outside to expel.

To get everybody in focus, Gruber tilts the lens downwards to use the Scheimpflug principle and get maximum depth of field by stopping the lens down to f/32.5 (the smallest aperture is f/128 and the largest f/8). Today photographers have been warned that f/32 will produce unsharp results due to diffraction, but that is for the much smaller 35mm full-frame format. For this huge format, f/32 is fine and, in fact, Ansel Adams even created Group f/64, in which members preferred to shoot at f/64 on large format cameras.

The 12×20-inch Film for Banquet Cameras

You can still (subject to availability) get fresh Ilford Delta 100 12×20 B&W ISO 100 12×20 film film these days. Banquet cameras today are being used more by landscape photographers to create panoramas, so Ilford can still do once-a-year film runs. And when available, Banquet photographers need to hoard it for future use.

LTI Lightside in New York City is Gruber’s go-to lab for developing the 12×20 B&W film.

“We have a contact printer, and that is by far the best way to proof [in the old days, often the final and framed] a shot,” says the banquet photographer. “However, if we are going to make an enlargement, we scan the negative and print digitally.

“For a wedding, I need to print larger than 12×20 for a wall print. So, I typically would scan and produce a 24×40″ or 36 x60”, mount it on aluminum, and as Jayson taught me include an inscription for the heirloom it immediately becomes and historically in 75 years.

“In 2004, I found a man in Chicago with a 12×20 enlarger. It took up an entire room and was used for printing books and making murals. He sold it for scrap eventually. I have a ten-foot print he made of my birthday [party] in 2003.

“Most scanners are not appropriate for banquet film. Anytime I have the budget, I send the film to Laumont Photographics in New York, who have a drum scanner that fits a 12×20 and can print huge and mount.”

In the past, Gruber has received requests for giant prints after being hired for things like weddings and corporate anniversaries, but people seem less interested these days.

When customers have asked for color banquet photos, Gruber has shot on his 8×10″ Deardorf camera as no color film is available in 12×20. He also prefers the “smaller” camera for groups under 100. Here he uses Kodak Portra-160NC with blue-coated lightbulbs.

Getting Into Photography

Gruber was given a Brownie camera when he was eight growing up in Pittsburg, Pennsylvania. His mother, Aaronel, was a painter and sculptor, who always carried a camera, but warned him, “Never become an artist!” His father made home movies of significant events like trips to DC or out west or Gruber’s birthday parties or swim races.

“I think I must have modeled my own photography habits after theirs,” reflects Gruber. “I carried my camera on trips, around campus, to concerts, to parties and weddings of friends.

“I was a film major at Vassar College, yearbook editor, fashion photographer’s assistant, author/photographer of three cat books, and went to Columbia Film School [MFA in Screenwriting and Directing]. My thesis film under advisor Martin Scorsese, “Not Just Any Flower,” was an audience favorite at the Sundance Film Festival. Stories told through photographs were always an interest of mine. I love portraiture and group portraiture the most.”

Gruber has loved collecting banquet photos since he was 20. Today he has a hundred or so that he has found in flea markets and vintage stores but mainly on eBay and about 40 that he has shot.

“In 2003, I met Jayson Jons, aka John Selepec, the only banquet photographer I could find, and hired him to shoot a 12×20 B&W banquet photo of my friends and family seated at my [50th] birthday dinner,” remembers Gruber. “Jayson was a colorful octogenarian from around Pittsburgh and asked me if I would like to assist him on the last remaining banquet jobs that he has been shooting since the 1960s.

“They were Associations. The Hats Association of American, the steelworker local, and two of the oldest white-shoe law firms in the city … I loved working with him and learning his process. The pressure was immense, and at 80, even with his wife at his side, he had trouble lifting the heavy equipment and mostly climbing up the 10-foot-tall ladder.”

Gruber started banquet camera photography in 2006 after his mentoring by Selepac. He was gifted (or sold for $500) one of Selepac’s 12×20 cameras, a 9-foot wooden collapsible tripod, and his secret sauce, the bulb lighting he had used since 1950.

In 1964 Gruber attended the 1964 New York World’s Fair as a 10-year-old. At that time, they went through Grand Central Station, and he remembers being wowed by the giant 18×60-foot Kodak Colorama at Grand Central Station, which was actually shot on a banquet camera.

In 1975 when he relocated to New York City, he was very impressed by the Coloramas.

“Yes, it is one reason I was attracted to the image,” he says. “I would stare at the print and marvel at the detail.”

After becoming a professional photographer, Gruber and his company achieved a high level of success — he has photographed many celebrity weddings, including Catherine Zeta-Jones and Michael Douglas, Billy Joel, Salman Rushdie, Padma Lakshmi, Geraldo Rivera, Jon Cryer, and Melissa Rivers.

In the past, Gruber used to get 3 to 4 clients for banquet photos per year, but last year it was only two.

Gruber has never found a historical image of a photographer shooting a large group with a banquet camera.

“And I have looked for years,” says the modern photographer with the ancient camera. If there really is no such photo that exists, the only image of a banquet camera photographer in action is Gruber.

Editor’s note: If you know of any such photo, please link it in the comments below—also, any other active banquet camera professional photographers in the US or Internationally.

About the author: Phil Mistry is a photographer and teacher based in Atlanta, GA. He started one of the first digital camera classes in New York City at The International Center of Photography in the 90s. He was the director and teacher for Sony/Popular Photography magazine’s Digital Days Workshops. You can reach him here.

Image credits: All photos courtesy of Terry Gruber

Author: Updated

Source: Petapixel