Back during CES 2024, Advanced Micro Devices announced its latest GPUs aimed at players who want to play the games of 2024. It also unveiled new CPUs and talked about a new era for AI.

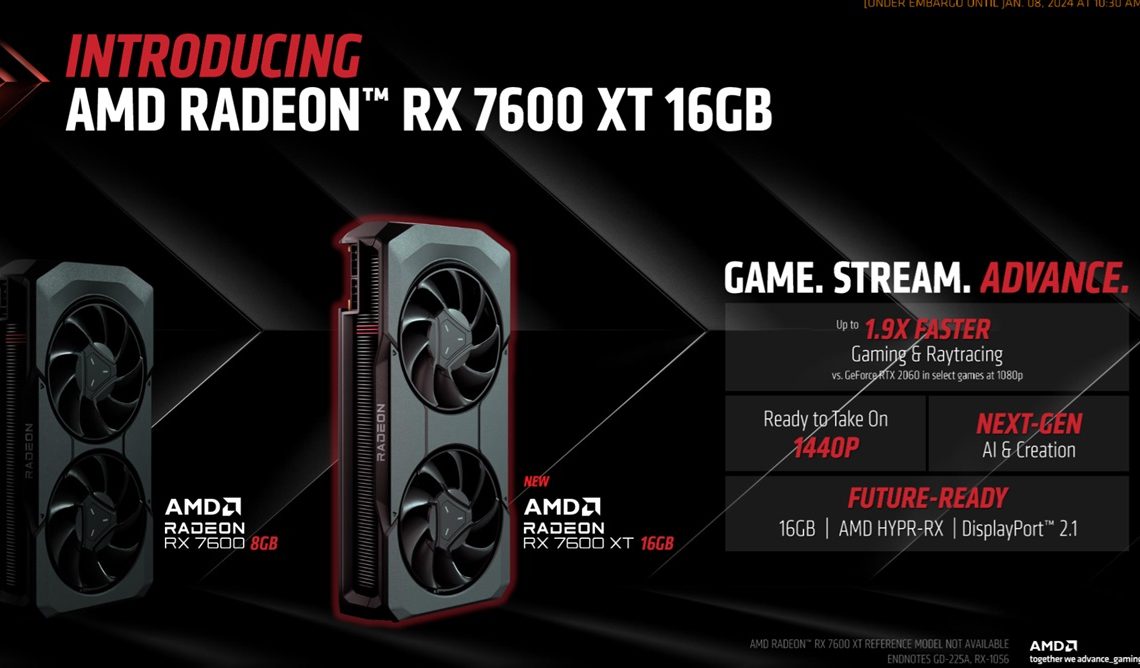

The new AMD Radeon 7600 XT 16GB and AMD Radeon 7600 XT 8GB are aimed at the middle and low-end of the gamer market — people who haven’t refreshed their gaming hardware in a while.

AMD noted that 50% of PC gamers are not having a great experience because they’re running big games like Call of Duty: Modern Warfare III, Starfield and Avatar: Frontiers of Pandora well below the optimal 60 frames per second at 1080p resolution.

AMD is also launching its AMD Ryzen 8040 Series processors, built on a foundation of neural processing units based on AMD Ryzen 8040 XDNA and central processing units based on the Zen 4 architecture.

GB Event

GamesBeat Summit Call for Speakers

We’re thrilled to open our call for speakers to our flagship event, GamesBeat Summit 2024 hosted in Los Angeles, where we will explore the theme of “Resilience and Adaption”.Â

The desktop processor will also be the world’s first desktop processor with a dedicated AI engine, AMD said, with a combined 39 TFLOPs of processing power. AMD said the AI processing will help with performance, security, efficiency and future costs. There are over 100 experiences optimized for Ryzen AI today, AMD said. It’s also faster on AI applications such as Stable Diffusion, Cinebench and more.

I talked to Frank Azor, chief architect of gaming solutions at AMD, about the new hardware, the impact on software, and the changes coming thanks to AI.

Here’s an edited transcript of our interview.

Frank Azor: The new 8000 series G desktop processors are a pretty huge improvement relative to the prior generation. The biggest things are the L2 cache increase, obviously the latest Zen processors as well, but the biggest leap is going from Vega class integrated graphics to RDNA 3 class integrated graphics. You take that raw horsepower of the RDNA 3 graphics that we put into these desktop processors, and then you tack on the software features we’ve been launching over the last few years as well, like Hyper RX, our Fluid Motion Frames technology, our Adrenalin software. They work on the desktop processors.

We’re seeing performance that’s pretty amazing. Definitely best in class performance for integrated graphics processors, and certainly in a desktop form factor. Mobile, you’ve seen some stuff, some decent graphics for a while now. But in desktop there’s nothing else like this in the market. Then we launched the Radeon 7600XT graphics card as well. Now it’s a little faster than the non-XT version we previously launched. It comes with 16GB of memory as well. It has all the RDNA 3 features, the same ones we talked about at the architecture day.

GamesBeat: I just met with a chip analyst from Accenture. He was saying that they’re starting to see more advances being made in software than in hardware sometimes with a lot of the new chip launches that are happening. I don’t know if those features you mentioned are actually implemented in software, but bringing them over to the new processors, is that giving you bigger performance increases than the changes in chip manufacturing?

Azor: I can talk a bit about it. I’m not a chip architect, so I’m not the expert. But I think the observation is fair. In probably the last four to six years, we’ve seen a lot of software innovation come into delivering pixels or optimizing power efficiency on the platform. Even upscaling video, different things like that. Opportunities have presented themselves and a lot of innovation has been applied there. I wouldn’t say that it’s necessarily because of anything going on from a process perspective, node processes. Those two things are happening in parallel, not necessarily one because of the other. They’re just happening.

Market reception has improved for some of these upscaling technologies and these alternatives now, for different reasons. Because of cost reasons, because of price reasons, because of the overall market condition, because the technologies have gotten to the point where they’re largely indistinguishable from raw computing power in a lot of cases. Graphics at least. All these different stars have aligned to make it more acceptable, or just more tolerable to be able to implement these software tactics, whereas before the focus was primarily on raw computing horsepower. The strategy was very simple. It was Moore’s Law, just try to shrink it in half, increase the density, and get a more powerful chip for a similar amount of money for the wafer. Maybe a bit of cost increase over time.

Those dynamics have evolved a bit. At the same time, some of these parallel tracks around software have been developing very well. We have solutions now, like frame generation, that are really good. You have upscaling that looks really good. But the interesting thing is that upscaling has been done with TVs for well over a decade. To most people it’s seamless. It’s hardly noticeable. But it’s a different environment. It’s 24 frames per second versus 60, or 60 versus 120. You’re not watching a TV from a two-foot distance. You’re watching it from 10 feet.

Gamers tend to be more sensitive to some of those tactics, but as I said, the technology has gotten so good. The tolerance around it has become more acceptable. People are open to these alternative methods of getting more performance out of their card, out of their silicon, than just buying more dense chips or bigger chips.

GamesBeat: If you look at the ways that things can advance, these displays that are running at 240Hz or whatever, that have .03ms response times, these numbers are dramatically different from years past. We’re getting more bang per buck out of some things that are different about the games of today.

Azor: What I would say around that–the most popular and most-played games out there in most geographies around the world, if you look at the top 20 games, roughly 15 of those games or so are not immensely graphically intense games. They’re not games that struggle to get to 60 frames per second. They tend to be esports-centric titles. With most modern graphics cards today, anything built in the last one or two generations, you can play those games at 100 frames per second or more.

Once you achieve–let’s say you buy the latest graphics card. It doesn’t have to be the most expensive one, but you spend $400, $500, $600 on a graphics card and you’re getting 200, 300, 400 frames per second in these games. If you don’t have a monitor to capitalize and take advantage of that, there’s no return on that investment. Then the natural thing to do is buy a monitor that lets you capitalize on the GPU investment you’re making, so you can benefit from the experience that it can offer you.

Depending on what you’re playing, that could be very appealing. If you’re playing a game like Starfield, the value of a 480Hz monitor is going to be little to none. But if you’re playing Counter-Strike, it’s going to be pretty high. To that competitor, to that gamer, they don’t want anything to be an impediment to their ability to compete. They want their skill and their ability to be represented in how they compete in the game, without any friction in between. Any point of friction that exists, as income comes in over time, they’ve proven that they’re willing to invest in reducing and eliminating that friction as much as possible. That’s given birth to these 240Hz, 360Hz, 480Hz monitors.

In my personal opinion, I don’t think we’ll see much beyond 480Hz or 500Hz. The returns diminish to a point that it’s not worthwhile. But we’ll see. I’ve been wrong before.

GamesBeat: The game that gave my machine the most trouble was Alan Wake 2. The visual quality had trouble when I was moving. Do you think of any particular games as occupying the very high end at this point, games that are challenging to run?

Azor: Starfield. Alan Wake 2 is very challenging. Cyberpunk has their modes, the tech demo modes that they have. Nobody is playing the game daily in those modes. It’s more like, “Let me see what my machine is capable of.” Avatar is a pretty challenging game as well. There’s a huge library of games, of course.

It’s still a dynamic where if you’re going to come out with a competitive shooter game, though, you want it to be playable on as many platforms as possible. That’s what’s interesting about the 8000G series processors. You can buy one component that has RDNA 3 graphics, and it’s obviously a great Zen-based processor as well. It starts to create an installed base, hopefully, of richer capable systems, without the customer having to buy two pieces of discrete silicon that cost more money.

What we hope will happen is that even some of the esports-centric titles, they’ll start to get a bit more graphically intensive as well. They’ll start to look better, evolve more in how they look, because the installed base is going to start to proliferate a bit better. Graphics cards have gotten more expensive over time. You don’t need me to tell you that. You can look at the prices in the marketplace. I think it’s incredible opportunity for a desktop-class CPU to come out and say–if you’re going to make an upgrade today and you only have a few hundred dollar, most people would immediately jump to the GPU, buy that first, and then wait until the very last moment possible to buy a new CPU and motherboard and memory. That’s the bigger expense.

Now we’re going to start to influence those decisions a bit differently. People may decide, if they have $400 or $500 for an upgrade, but they have a PCIe Gen 2 platform that they’ve been putting graphics cards into and they’re still running DDR2 memory, maybe they should spend that money on a new platform instead. They’ll get decent graphics capability out of it for a while with an all-in-one solution at an incredible value. Then, when you save up a few hundred dollars again, you drop a new graphics card in there and get the best of both worlds.

The richer installed base of integrated graphics, I’m hoping–it’s not these titles that we’re talking about here, but we’ll try to drive some more graphics improvements in these more competitive esports types of titles. In some cases, they haven’t evolved a lot in almost a decade. They want to be able to run on everything that’s out there. They want player count. And you’re playing that game for different reasons.

GamesBeat: What do you think about this era of the AI PC that Intel has been talking about? Are you also, to some degree, pushing the idea that there’s a new wave of applications coming for consumers, because there’s more AI processing happening in PCs? Are we ready to market PCs as AI PCs?

Azor: Absolutely. I believe so. This is a big conversation, but–it’s not just Intel that’s marketing AI PCs. We absolutely are too. I think we launched the first AI CPU when we launched last year, with Ryzen AI. We may have the most AI-powered PCs out there in the marketplace, because we’ve been shipping them in for almost a year now. We do believe in it.

AI PCs, it’s hard to draw a direct analogy, because it’s a very different thing compared to the internet or multimedia, things like that. But the best way I could describe it, looking at historicals–would you want to buy a PC today that was not an AI PC? If it’s a laptop, you’re expecting to get three years of life cycle out of it. If it’s a desktop, five years maybe, six years of life cycle out of it. The way I try to explain this to people when friends and family ask me, imagine buying a computer without an Ethernet port or Wi-Fi in 1998. You would have been kicking yourself. You’d have a product that wouldn’t be able to grow with these emerging use cases that were coming very quickly to the platform. It would be obsolete very quickly.

For a lot of people, what’s important for them to consider right now is, the AI revolution is not coming. It’s here right now. I can say this confidently. Nobody knows the full extent of how this is going to transform the world. The full extent of it. I think everyone understands little pockets of it. But to try to wrap your head around the potential of the AI PC is like trying to wrap your head around what the internet could do when you first discovered it in 1992 or 1993. You connected, you opened a browser, and a web page popped up. I can’t imagine that someone thought to themselves, “One day this will be in everyone’s pocket and they’ll all do their finances and communication and education with it.” It transformed almost everything we do. It’s a fundamental technology. I know AI is that.

It’s one of those things where it’s better to be safe than sorry. Even if you don’t know for sure how you’re going to apply it in your life, if you’re making a PC purchase today, the safe bet, the smart decision is to going to be, get one that’s AI-capable, because what’s coming–at some point you’re going to want that capability. You’ve seen what Microsoft is doing. You could say that they’re only on version 1.0. They’re doing it very quickly and very aggressively. You can start to brainstorm in your own mind, what will version 2.0 or 3.0 look like? What’s the timeline for that? Version 2.0 isn’t going to happen in 10 years. It’s going to happen quickly.

GamesBeat: For something like Copilot, do you know if it’s going to use the AI processor in the PC? Or will it just use Microsoft’s servers?

Azor: The answer is both. There will be use cases that will make use of localized AI compute, and there will be use cases that rely on the cloud. But customers who don’t have localized AI compute will have a severe experience detriment relative to people who do.

GamesBeat: Some people have brought up that there are also reasons you want AI on the edge, because of privacy and other concerns.

Azor: Privacy and security, absolutely. Again, I try to simplify things as much as possible. If localized AI, local AI compute wasn’t necessary or valuable, if it wasn’t going to have an experience impact, I would draw a parallel and say, why do we have any localized compute at all? Why aren’t all of our devices thin clients? The reason, as we all know, is because when we have tried that in the past, the experience hasn’t been great.

You can get to about 60% of the experience, maybe 70%, but when you want the 100% type of experience that we use with the compute available to us at any time, in any situation, in any environment, you need localized compute. Nobody has been able to put a CPU at mass scale in the cloud and create a practical end user thin client kind of environment. Mass scale is the key. It’s been done in pockets, of course. It’s the same with AI compute. It’s the third chip, if you will. You have the primary CPU, the brain, and you have the graphics. Now all these emerging use cases are coming. It’s as if all these new games are coming. Could you imagine being a gamer and you don’t have the GPU to play them? That’s the environment that’s emerging very quickly.

It’s not about–if I bought a computer a year ago, and I’m not in the market to buy a computer today, should I immediately go out and buy an AI PC, even if there’s no immediate AI use case for me? Maybe not. That’s not the message. It depends on what you’re using. What AI workloads are you going to be using? Do they run on graphics or do they run on NPUs? What you’ll initially find is that there’s going to be a fair amount of fragmentation. There won’t be synergy across the two architectures. I’m not saying this from an AMD perspective, but the entire industry.

Read More: AMD Unveils Xbox Series X Ports in Action!

Most discrete graphics is going after developer and creator types of workloads. The NPUs within the CPUs or APUs are going after more end user, consumption, non-professional creator use cases and applications. It’s almost like workstation-class graphics and the workstation style of compute and workloads, and then you have consumer types of workloads. That segmentation is going to happen initially, and then I think we’ll converge as an industry at some point in the future, maybe to common libraries and common capabilities between the two different segments of the market.

Author: Dean Takahashi

Source: Venturebeat

Reviewed By: Editorial Team