![]()

In 2018 with some trepidation I bought my first mirrorless camera, a Nikon Z7. It wasn’t because I thought it was better than the DSLR I had been using but because my old muscles were spasming with the weight of the camera I was using and I hoped that a package a pound lighter would help me keep on working.

Then slowly I began to learn what I had bought — a camera with major advances over any camera I had ever owned, film or digital. I hadn’t expected that. Now two years in, I’ve shot enough to see the advantages of mirrorless and I’m ready to share what I’ve learned, so — here we go.

They are lighter — Mirrorless cameras are significantly lighter and sometimes their lenses are lighter too. Don’t kid yourself, lighter is important even if you don’t feel the weight as an imposition. Cameras are inherently unbalanced with their mass extended from your body. We learn to hold them close and use the left hand to provide a second mounting point. But at the end of a long day, your muscles get tired and when they do, less mass means smaller micro tremors — and maybe the desire to shoot a few more frames.

A modern lens mount gave me better lenses — I loved my old Nikon lenses and I planned on using them on the new body with an adapter. It was the progression I had come to expect as I upgraded through the years. But I bought one lens made for the new mount, and shooting with it blew me away. I quickly saw how much better the images were and all my old lenses started looking … old. Yeah, it cost me some money as I sold off old lenses and replaced them with new ones but boy am I happy with the results

That new lens mount opened another door too, the ability to use old lenses from any camera, regardless of manufacturer. Getting rid of the mirror mechanism moved the mount a lot closer to the sensor, leaving room for adapters to almost any old lens, so I could have my new glass for that perfect look and my old glass to take me back to another time.

In-body stabilization transformed the old lenses I kept — I didn’t sell all my old lenses, just the modern ones. I love to shoot with really old glass, lenses without coatings, and simple optical designs. I love their flares and their soft contrast, and their bokeh. The first time I mounted an old single element 100mm lens on the new body I was stunned by how different it was to shoot with it. The in-body stabilization turned it from a shaky, use every trick I knew experience into a solid shake-free image. I had been shooting with lenses like this forever but this was a brand new experience.

Seeing in the dark — Modern cameras have an astounding low light capability, much better than our eyes, and as a result, digital cameras have far outstripped our ability to see in the dark. When I was still shooting with my last DSLR I peered into the dark viewfinder, made blind guesses, clicked the shutter, then waited to see the image on the back to know what I had shot. With mirrorless, the viewfinder tells you what the image will look like, not what the scene looks like.

Focus Peaking — Of course, none of my old lenses had focus motors, and here is another place mirrorless really helped me out. The combination of clicking in to see a 100% view and focus peaking on demand has made keeping old lenses in focus a dream. Now, when I’m working close I can just rock back and forth until peaking shows me the focus is where I want it, and bang I’m shooting. No optical viewfinder does that as well, except maybe shooting with an old Panaflex where I could switch in a magnifier to check critical focus.

Presets have changed the way I work — Shooting film, I learned previsualization early on. I spent time thinking about how scene brightness would translate into tonal values on paper, remembering which colors would pop in the print. Now, with preset looks, I respond directly to the image in my viewfinder in the same way I respond to movement or emotion. Instead of an intellectual understanding, I have an emotional response to what’s going on. It’s “WOW, I love this … or This sucks, what would be better” right away. DSLRs have presets too but you can’t see them until after you make the shot. Seeing presets in the viewfinder is a game-changer.

A quiet shutter gives me more useable pictures — No mirror slap means no people turning to see what just happened. Even when I’m doing portraits there‘s fewer of those involuntary flinches that people often make when a camera goes off close by. And when I’m shooting at slow shutter speeds no shutter slap means one less source of vibration to mess up the shot.

A camera that lets you see what you’ve done lets you play more too — Instant review is a wonderful thing, especially when you are playing with time. DSLRs offer this too, but only on their back screen. And working in bright sunlight the back screen becomes useless for making any kind of critical judgment. For instance, seeing the difference in blur between a third of a second and a quarter second exposure is virtually impossible. Looking through the viewfinder is so much better. With no stray light and the image filling your eye it’s easier to see the details, to respond emotionally, to make better changes.

Tightening the loop — In the world of remote controls, a place where I spent some of my life, we call all these differences tightening the loop. What that means is knowing when something varies from a desired result and more quickly making a change that results in a better outcome. When we shot film the only way to tighten the loop was slop processing, dunking a bit of film into chemicals on-site to see what was on the negative right away. Then Polaroids tightened the loop as did video assist on movie cameras. But the big change came with digital cameras. They made a lot of people better photographers even if they didn’t know exactly why. The complaints from purists were legion, “what are they doing checking the back screen all the time, it’s too late when you’ve already made the picture” … and of course they were right about that … but it was not too late to learn from what they had just done. In fact, it was the best possible time to learn, right now, at the moment when you clearly knew what you had desired and how the picture you had just taken disappointed you.

Summing up — I’m expecting I’ll hear from some of my friends on this story. We spent our lives learning how the human eye and the camera saw differently. We learned how to be analytical when judging a scene, how to stand back and use our understanding to judge what would be transformed by the camera, the stock, and the light. In Hollywood, cinematographers didn’t even look through the camera at the moment of shooting. Instead, they stood next to it using their judgment and knowledge to imagine what the scene would look like the next day in dailies, and they were almost always right. But things are different now. … we have a new generation of cameras that show us exactly what our picture will look like even before we take it. Seeing exactly what the camera is going to render while looking through the viewfinder is enormously powerful to me, a transformative technology. I love it and I won’t be going back.

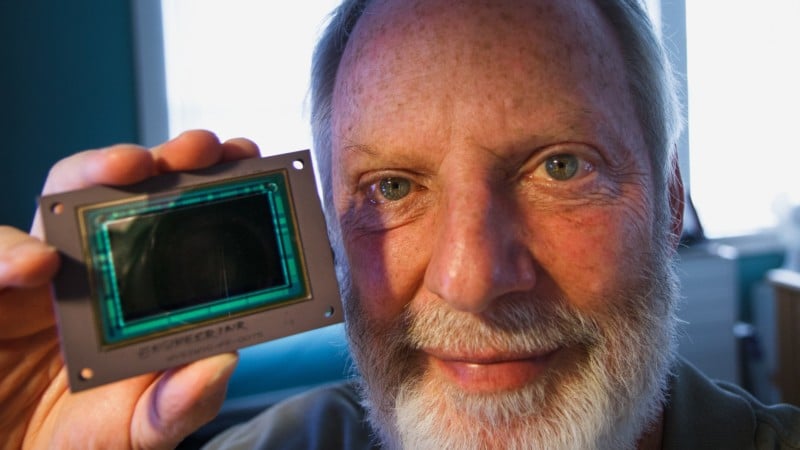

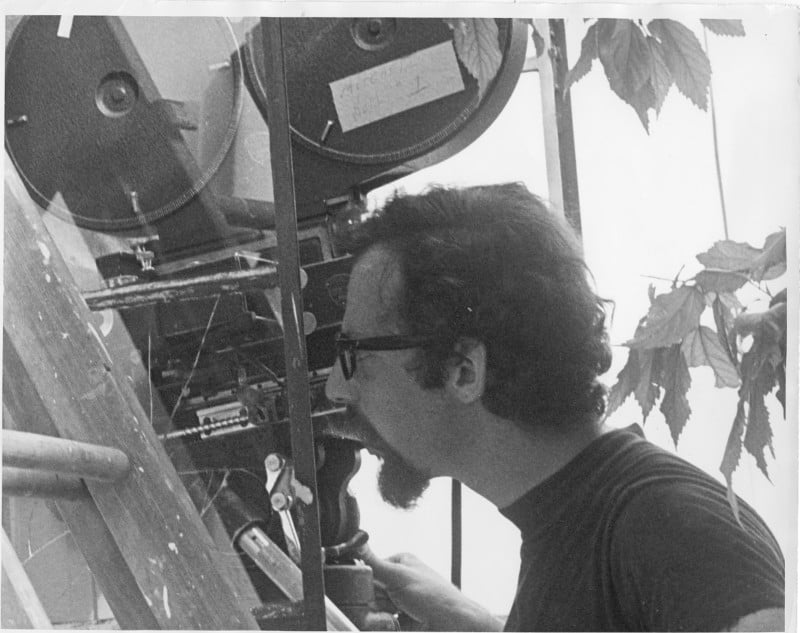

About the author: Andy Romanoff started taking pictures over sixty years ago. He has shot using cameras of every description including box cameras, rangefinders, SLRs, TLRs, view cameras, DSLRs, and movie cameras from Aaton to Panavision. Now he is shooting with a mirrorless camera while he waits for what comes next. Andy writes about photography for L’oeil de la Photographie, Stories I’ve Been meaning to Tell You, and Petapixel. He lists his photo sales here and you can subscribe to his YouTube Channel here.

This story was also published here.

Author: Andy Romanoff

Source: Petapixel