![]()

Android phones appeal to many — from affordable low-end devices to higher-end models with all the bells and whistles. But why are Android camera apps still nowhere near as good as iOS? Are Android users always going to be a step behind?

In January, PetaPixel released a guide for the best Android camera apps in 2022. However, in stark contrast to the best iPhone camera apps guide, we found that Android’s offerings were notably weaker. It took considerably more time and effort to come up with recommendations we were confident in, and it got us thinking about the issue. Why was there such a chasm of difference between camera apps for iPhone and those for Android?

After some investigation, we found that it wasn’t because Android app developers don’t listen to what users want, but because they face numerous limitations during the development process that greatly hinder development capabilities.

Harshit Dwivedi, the founder of Aftershoot, an AI-powered culling software for photographers with extensive experience with the Android operating system and application programming interfaces (APIs), shares his insight to help explain the difficulties developers face when creating apps for Android users and why it can feel like Android users are a step — or several steps — behind a photographer with an iPhone.

The Android Market is Too Diverse For Its Own Good

Dwivedi views the issues Android devices face compared to iOS as similar to delivering apps on macOS versus Windows. The issue in both cases is fragmentation.

For example, all of the macOS and iOS devices available on the market today only have set screen sizes.

“You wouldn’t have an iOS phone running a 10-inch screen or a weird aspect ratio, but with Android, that is the case,” says Dwivedi.

If a developer built an app on an Android phone, they cannot guarantee that it would work the same manner on other Android phones, such is the case even for simple image gallery apps. This issue arises from the orientation flag found in the image metadata, which determines whether a photo should be flipped or not.

The value for that orientation flag is different on a Samsung phone versus a Pixel phone versus a Xiaomi phone, and so forth. Even using the same code, an image that looks upright on a Samsung phone can appear 90-degrees rotated on a Xiaomi phone. This brings a host of issues for both Android developers and smartphone users.

Android is also open source. This means that a developer can take what Google has done and add custom features, change the basic functionality, and repurpose it. But that’s not to say that apps will always perform on all Android devices equally.

For example, Xiaomi has a power saver mode that disables all the background functionality for all the apps. If a user has Whatsapp running in this power saver mode, they wouldn’t receive any notifications unless the app was already opened. This is just one example of how apps behave differently because of the changes a manufacturer makes.

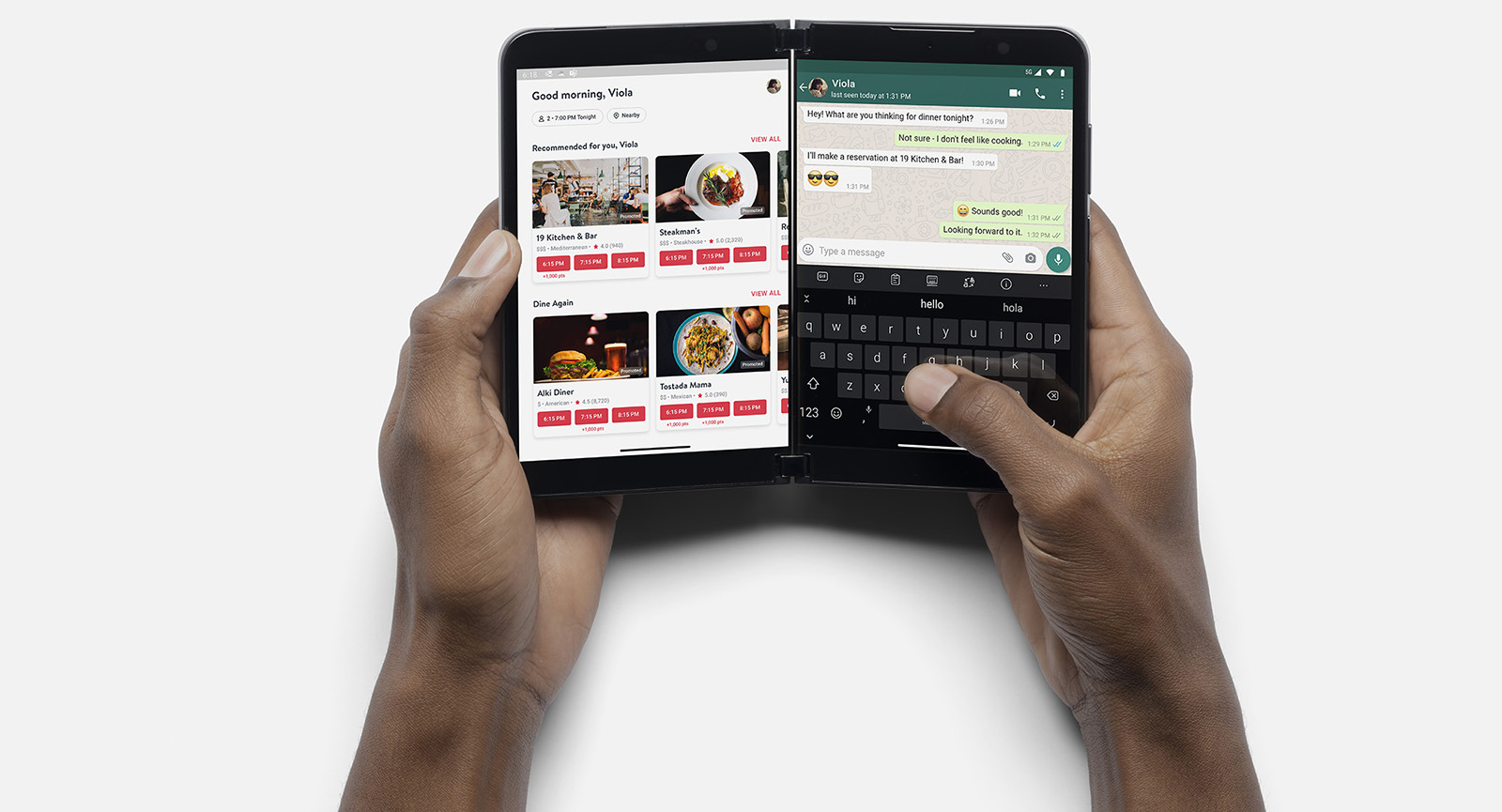

Some companies will provide hooks for developers to use. These hooks give programmers the option to add custom code that allows modifying the behavior of a program. Dwivedi uses the LG Wing phone as an example. The smartphone features a dual-screen display that rotates the top screen into a landscape position and reveals a smaller screen underneath.

“I’m sure they have hooks for developers to use to understand when the phone’s form factor has changed or when the phone has done a specific thing, but it presents a problem,” says Dwivedi. “What incentive do I get to support that particular phone as a developer? I don’t — that feature is just a gimmick.”

“You cannot be both the hardware provider and the app creator. LG doesn’t have the bandwidth to do everything — the company cannot go and make all the apps for these phones. Instead, they need to allow developers to build features for those phones.”

To put it into perspective, if Apple said “no developers allowed, we will build all the apps for iPhone,” users would only have a tiny fraction of the apps currently available.

This problem also sheds a different light on the various Android models that have been patented or come out flaunting unique designs, like Xiaomi’s modular design, Fujifilm, Huawei, and Samsung’s foldable smartphones, and others.

While they may look eye-catching and futuristic, users still need to be cautious and consider their priorities when buying a new Android phone. If top-quality camera capabilities are important, will they be leveraged in unconventional design phones? Similarly, how essential are practical use and support?

In the case of LG Wing, the situation is bleaker. In 2021, LG announced it was officially walking away from producing phones, leaving LG Wing users in an even less favorable position.

Android Buyers Face Hidden Surprises

Shopping for Android phones is not easy for consumers to navigate. Clever marketing tactics might disguise things that the user isn’t even aware of, even if they have done extensive research.

For example, buying a Samsung Galaxy S21 in the United States will differ from the same phone bought in Europe and India. Those buying from the United States will get a Galaxy S21 with a Snapdragon processor, but the same phone comes with Exynos processor in Europe and India, built by Samsung in-house. As a result, this difference affects image processing.

Dwivedi says he doesn’t blame users who may get confused because “it’s the company’s job to advertise correctly.”

Similarly, if a user sees a phone advertised as having a 10-times optical zoom, the user shouldn’t have to know the ins and outs of the technology underneath. Instead, the product information should be accurate and accessible. This is not always the case, and there is not one overarching group that manages these kinds of expectations across Android devices like there is for all devices running iOS.

Which Android Phones Look the Most Promising For Photographers?

For anyone serious about professional photography and looking to buy an Android phone without investing in a DSLR or a mirrorless camera, Dwivedi recommends the Sony latest smartphones, such as the Xperia Pro I or the Xperia Pro.

“They have been doing impressive things with their cameras [for professionals], and plenty of Samsung phones use Sony sensors,” he says. “It’s a niche market, but that’s the market Sony has been going after.”

For enthusiasts and general users who want “nice-looking photos,” Dwivedi recommends Google Pixel phones — such as the Pixel 6 Pro — which utilize AI tools to enhance photos on the go.

When it comes to mid-range Android phones, Dwivedi has noticed their cameras are not great, to put it mildly. Some phones have numerous cameras on the back, yet they don’t perform well and are “mostly gimmicks”.

For example, having used a middle-range Android with three cameras and later a Google Pixel smartphone with just one camera, Dwivedi instantly noticed the drastic difference in quality between the two, with Google Pixel coming out on top.

“It’s not about how many lenses you can fit on the back of the phone,” he explains.

Also, the users that these phones target don’t necessarily prioritize camera quality. Instead, factors like the battery life or using multiple apps with no lag take precedence. With that in mind, it makes sense why photographers may be frustrated with the lack of image quality on a mid-range smartphone and why companies don’t focus on image quality for these devices.

“The moment you try and use a camera provided by any other app, it lacks advantages, like HDR processing,” says Dwivedi. “That’s the biggest ‘con’ I’ve noticed for Android whereas with iOS, regardless of which app you use, the quality is top-notch.”

This also echoes the sentiments of Josh Haftel, who was director of product management at Adobe. He also noted that Android smartphone cameras are a “nightmare,” according to Dwivedi.

The Future of Android Smartphone Cameras

To look at what’s ahead for Android smartphones, it helps to look at the problems that have persisted so far. From a developer’s perspective, Dwivedi notes that if his job is to make the best camera app for Samsung phones, he can do that. But, if his job is to make the best camera app for all Android phones, that’s when things become difficult.

For a custom camera, developers have to use Android Camera API — the first version, Camera1, supports devices older than Android Lollipop, and the second version, Camera2, is supported only on Lollipop and newer devices. However, both present different difficulties. For example, Camera1 is more basic and lacks functionality, while Camera2 is notoriously difficult to work with, says Dwivedi.

![]()

To combat this, Samsung original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) made APIs for developers, such as for Snapchat, and instructed them to skip Google’s API and use its API instead. However, the issue is that doing so is that the apps developed this way only work on Samsung phones.

That means that developers need to make an additional “if-else” case — if it’s a Samsung phone, do this, if it’s a different phone, do something else. This quickly becomes hard to manage.

“I wouldn’t say it’s the OEMs fault. It’s Google’s,” says Dwivedi. “It’s Google’s job to build an API that leverages those functionalities and lets the developers easily call a function, which is what iPhone does.”

There is light at the end of the tunnel. Last year, Google added CameraX, which promises to help fix the problems in Android camera apps so far, like HDR processing. However, the API had been unstable up until July of 2021.

It hasn’t even been a year since the first stable release, so it’s still early days. Large apps like TikTok, Snapchat, and Instagram wouldn’t even touch it because they would only use a stable API to avoid potential risks and issues, Dwivedi says.

He believes that moving ahead, many apps will switch to CameraX now that it is stable, which will deliver a better image quality from Android camera apps overall.

The optimist in Dwivedi says that the gap between Android and iOS in terms of image quality from camera apps will close, but the realist in him thinks it will take quite some time to get there.

Image credits: Header photo licensed via Depositphotos.

Author: Anete Lusina

Source: Petapixel