Photographer Calvin Grier is a master of the alternative photography process known as carbon transfer printing, but for the past few months, he has been taking things to a new level. Grier is creating full color photographic prints using dirt.

Carbon transfer prints use pigmented gelatin to form the images rather than chromogenic dyes. Grier spent hundreds of hours and thousands of dollars researching pigments before finally settling on which dirt to use for which colors.

In the 10-minute video above, Grier explains the process and shows the creation of a print from beginning to end.

For his five basic colors, Grier uses red ochre from Morocco, green earth from France, yellow ochre from France, carbon black from soot, and lapis lazuli — the last one is a semi-precious stone that’s ground up, since blue is difficult to find in nature.

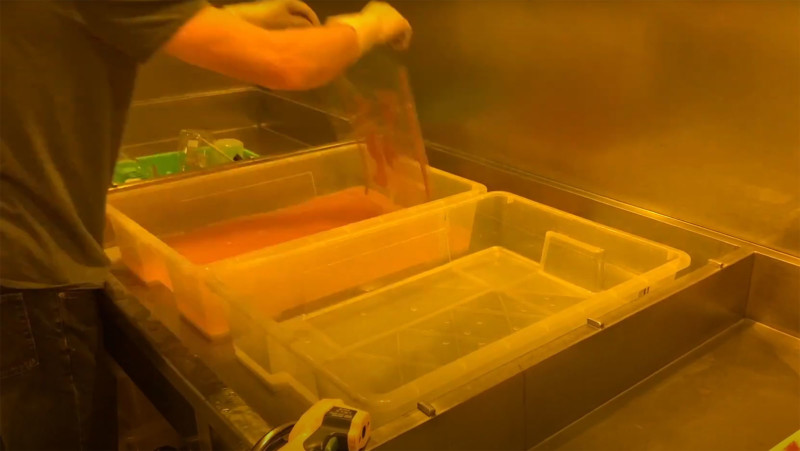

After grinding the earth collected into an extremely fine powder, he combines each one with water, gelatin, sugar, and a light-sensitive salt to create photographic emulsions. Coatings of the emulsions are then used to create photo-sensitive films.

![]()

![]()

![]()

The photo to be printed starts as a standard digital RGB file, which Grier then converts to a multi-channel profile. He creates 10 negatives representing the different channels and then prints them onto silver-based photographic film using a precise laser.

![]()

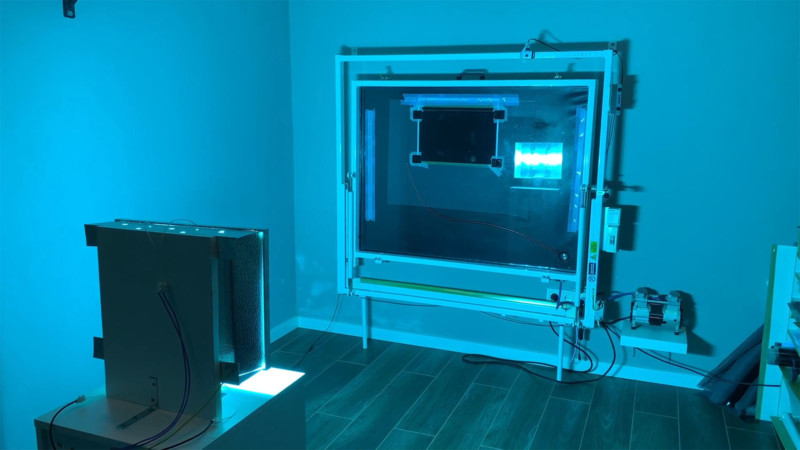

A high-powered ultraviolet exposure unit is then used to expose each emulsion with its corresponding negative.

Areas of the emulsion that are exposed to the UV light have free radicals released, which hardens it and prevents it from washing away in hot water. Non-exposed areas will easily wash away from the film.

As each emulsion layer is joined to the temporary support, the true colors of the photo begin to appear.

Each layer takes about 1.5 hours, so printing a single photo takes a whole workday.

Once all the emulsion layers have formed the full-color photo on a temporary support, what remains is to get it transferred onto its final medium.

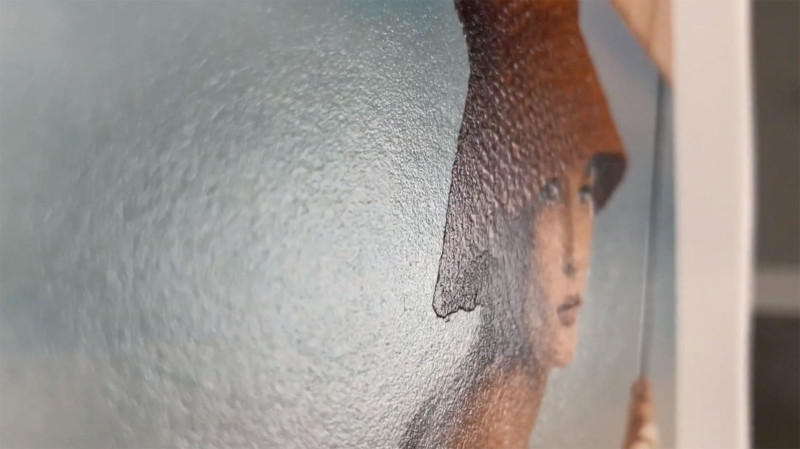

The resulting prints have some amazing attributes. Firstly, they’re much smoother than even the highest quality inkjet prints, Grier says.

![]()

They’re also extremely stable.

“Earth pigments have been exposed to oxygen, ultraviolet light, [and] acids of the atmosphere for thousands or millions of years, so they tend to already be in their most basic form,” Grier says. “They’re not going to decompose or fade like many synthetic pigments. This is probably the most permanent color photograph in existence.”

You can find out more about Grier’s printing on his website, The Wet Print. Grier says he plans to continue perfecting this process over the coming years.

Author: Michael Zhang

Source: Petapixel