![]()

Prior to the advent of social media and smartphones, and on the cusp of the shift to digital photography, the world witnessed September 11, 2001. Visually captured in a way that no single event had been documented before, 9/11 has been seared into our collective consciousness.

Each year, the anniversary generates galleries of images and videos that replay the day in exquisite and excruciating detail, yielding a mix of emotions from horror to sadness to relief.

In 2019, journalist Garrett Graf stated in a C-SPAN interview, “You know, this is a particularly interesting and momentous anniversary this year, because we are seeing this shift nationally of 9/11 from memory to history.” The “whatever happened to” pieces had been written, the government reports had been published, and history textbooks had already condensed the chaos of the day, the circumstances that precipitated it, and the aftermath into a few brief paragraphs like a yearbook entry for any other 18-year-old.

Listen: In the above episode of the PhotoShelter podcast, Vision Slightly Blurred, Sarah Jacobs and Allen Murabayashi discuss the continuing role that photography plays in the events of September 11.

The twentieth anniversary has emphasized this transition from “memory to history,” and it has also provided people and organizations a moment to reflect with two decades of hindsight. My social media feeds were filled with individual photos and galleries of the visual history serving both as a collective recollection as well as catharsis from the terrible day.

The Iconic Photos

Everyone from seasoned photo editors to the average person seeks to distill the complex into something digestible, often by trying to identify a single or set of “iconic” images. These images often acquire monikers like “The Catch” or “Napalm Girl,” handy mnemonics to instantly recall an event and visual association.

The knee-jerk reaction to “memorialize instantly” an image – as writer Lynne Tillman observed – can be problematic without time and context. Yet many of the images that were iconic twenty years ago have stood the test of time.

Robert Clark’s sequence of UA 175 hitting the south tower. Suzanne Plunkett’s men running from the collapsing tower. Shannon Stapleton’s image of firefighters recovering the body of Father Mychal Judge. Alex Webb’s photo of a neighbor with her child on a Brooklyn rooftop. Jim Nachtwey’s north tower collapsing behind the Church of Saint Peter. Stan Honda’s “Dust Lady,” Marcy Borders. And of course, Richard Drew’s “Falling Man.”

But unlike a single moment in a sporting event that turns the tide to a surprising victory, there is no one image that can encapsulate 9/11. Images of the towers are spectacular and sometimes strangely beautiful, but they don’t capture the human suffering and confusion. Similarly, “Dust Lady” doesn’t capture the scope of destruction.

Why Share Photos Year After Year?

The rallying cry of “Never Forget” was never solely a plea by history professors to recognize the importance of historical events. It was always heavily tinged with a sentiment of revenge and retribution. But twenty years later, Osama bin Laden and Saddam Hussein are dead, al Qaeda is virtually non-existent, and the U.S. has retreated from Afghanistan.

So why continue to share photos?

For photographers who captured the day, sharing photos offers catharsis, social proof that they were there, and a reminder of history. Photographers like Aristede Economopoulos also used the twentieth anniversary to publish unseen photos – suggesting, in part, that there is still a portion of the visual record to be revealed.

View this post on Instagram

Prompted by Economopoulos, I revisited some of my own photos and republished images that I hadn’t been ready to share for a myriad of reasons, including a discomfort with the “suffering of others.” But perhaps that shift from memory to history that only the passage of time can achieve has provided me with some solace.

View this post on Instagram

This year I also observed many friends sharing images in and around the towers: memories of makeshift memorials, special meals at Windows on the World, or vernacular photography featuring the towers as background elements.

Photography, it seems, provides people with a powerful connection to the day. It is more readily digestible and viscerally evocative than a written essay.

Back to the Corner

On September 10, 2021, I took the 1 train to the Cortlandt/WTC stop, emerging through the Fulton Transit Center – a $1.4 billion transit hub and shopping center that was opened in 2014 to help rehabilitate the Fulton Street station after 9/11.

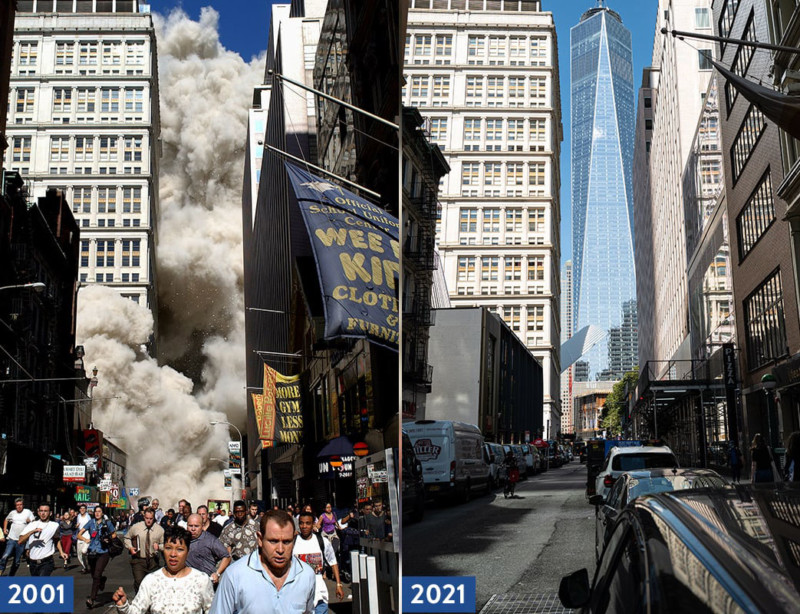

In 2001, I lived at Broadway and Rector Street in Lower Manhattan and wandered out to take photos after the media initially reported that a “small commuter plane” had hit the towers. I never really knew exactly where I was when the north tower collapsed, but I spent the night before on Google Maps Street View identifying landmarks and orientation based on a photo I had taken at 10:29am twenty years earlier.

As I stood on the corner of Fulton and Nassau Streets and pulled up a camera to my face, I had a strange sensation of sameness. The telephone booth and old street lights were long gone. And although half the buildings on the block were gone, the historic Western Union Telegraph Building still anchored the left side of my frame.

And on a day with eerily perfect weather and a cloudless sky that was perfectly reminiscent of 9/11, I saw a gleaming tower of glass – One World Trade – that stood where a cloud of debris had previously barreled down the street.

I hadn’t consciously revisited this spot in 19 years and 364 days. I felt no panic despite a very vivid recollection of the day two decades earlier. After I took a few photos, I was struck with the realization that the passage of time had slowly turned my own memory into history.

About the author: Allen Murabayashi is the Chairman and co-founder of PhotoShelter, which regularly publishes resources for photographers. The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author. This article was also published here.

Author: Allen Murabayashi

Source: Petapixel