A war in Europe instantly creates parallels with the world wars for people in the UK and other European countries. This connection represents what most people know and are taught about conflict on the continent.

The media coverage and response to the war in Ukraine have also invoked familiar images of the second world war, in particular those of bombed buildings, armed soldiers and civilians, and children clinging to their parents.

Our automatic response to images of conflict is often biased. We search for familiarity, for ways to process the horrors that are happening in front of our eyes, to answer our knee-jerk question: does it affect us?

Invoking images of the world wars arguably heightens our response because national ideas about the world wars are so deeply rooted in our historical knowledge. Yet wars in Syria and elsewhere are more easily seen by most Europeans as distant or foreign.

However, many of the world war battles involving European powers were fought outside of Europe, in places like East Africa and the Middle East. And of course, other wars before these were fought all over the world. This made us wonder: is the war in Ukraine different because it is in eastern Europe and undoubtedly invokes our knowledge and recognizable images of the world wars?

These questions are the focus of our new project, Early Conflict Photography (1890-1918) and Visual Artificial Intelligence (EyCon). In this project, we are exploring our westernized view of the world wars and how that is directly tied to the current inaccessibility of historical photographs and their contexts. To understand and correct this imbalance, EyCon is using artificial intelligence (AI) to improve our knowledge of often-overlooked war images from the early conflict era, from 1890 to 1918.

By capturing these graphic images and making them a part of our accessible history, we can start to recover overshadowed but globally shared experiences of war. But we can also question what effect our limited and Eurocentric knowledge of global history has on our response to images of modern conflicts.

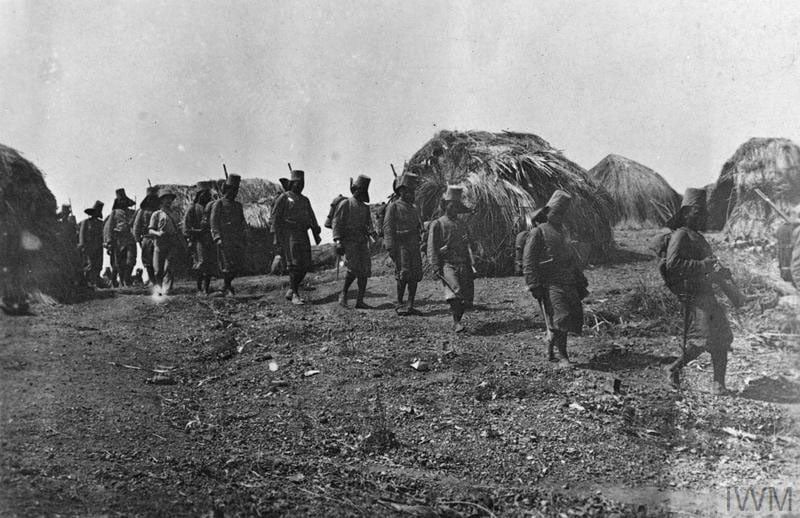

As part of Eycon, thousands of photographs from colonial warfare and pre-1914 conflicts, such as the Russo-Japanese war and the Balkans war, as well as first world war African and Asian battlefields, will be featured in the project’s database. However, it’s not as simple as uploading them.

Recording History

While a photograph might say a thousand words, those words are not necessarily the right ones. Conflict and war zone images create further issues for preservation and digitization, as they may depict sensitive material and there are often more than two sides to the story.

This means the interpretation of an image can become a matter of perspective. Without accurate information about the photos such as when and where they were taken (known as metadata) or the means to search images across archives, the full records of even our recent global conflicts could be lost.

The accuracy of metadata is one of the biggest problems with image preservation. While this data allows images to be discovered with keywords, the information that accompanies an image record can become problematic if the description and information are limited, outdated, biased, or simply wrong.

When historical images are digitized, much of the metadata is simply copied from notes on the original source held at the archive from which they come, if there are any notes at all. Another archive with a copy of the same image might have different notes, so the metadata attached to the digital record does not always match.

This is a major issue for archivists, researchers, and public users alike, as the accuracy of the record is integral to the way the photograph is used, cataloged, and interpreted. So when differences occur, how can we know which notes, if any, are correct?

This issue is the focus of the EyCon project. By applying AI that can analyze images to archival collections of early-era conflict images, the project aims to collate image metadata and identify inconsistencies or examples where more accurate metadata needs to be applied. This is especially important when the same images are held in different archival collections.

Two Different Stories

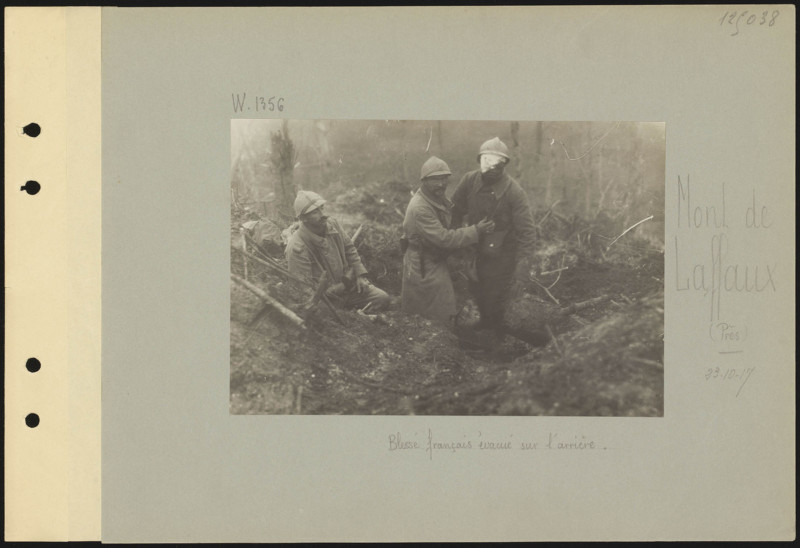

Take this image of three soldiers from October 1917 during the first world war. In simple terms, this is a photograph of male soldiers on a battlefield and one man is injured. The photograph is held by two French archives, La Contemporaine and République Française Images Défense.

The Images Défense record describes the photo as “Un tirailleur sénégalais est blessé au ‘Balcon’, position allemande conquise par les alliés près de Soupir” (“A Senegalese rifleman was wounded at the ‘Balcon’, a German position conquered by the Allies near Soupir”). However, La Contemporaine presents the following description, which is handwritten under the image: “Blessé français évacué sur l’arrière” “(French wounded evacuated to the rear”).

These different descriptions, listing the wounded soldier as “Senegalese” and “French”, highlight not only the discrepancies between historical image metadata, but also the very real potential for colonial troops to be written out of European history. Without the right context, and without further investigation, the real stories of these people can easily disappear.

While EyCon is specifically investigating early conflict imagery, the aims of the project – to develop visual AI techniques to source, collect and improve metadata for photo archives – can help to inform future projects with similar goals. For now, by bringing together global collections of early conflict images, identifying new photographs, and collating contexts and histories, EyCon’s open-access database hopes to correct and realign our heavily westernized and Eurocentric view of the world at war.

About the author: Katherine Aske is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow in the Department of Communication and Media at Loughborough University. Lise Jaillant is a Senior Lecturer (Associate Professor) of Digital Humanities at Loughborough University The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author. This article was originally published at The Conversation and is being republished under a Creative Commons license.

Author: Katherine Aske and Lise Jaillant

Source: Petapixel