![]()

A Wyoming-based photographer has uncovered a large collection of family photographs taken throughout the 20th century and digitized them to reveal and preserve the everyday lives of past generations.

Zachary Ian Peabody, based in Powell, Wyoming, is a photographer who discovered that his family has had an interest in photography throughout generations when he came across boxes and albums full of old photographs and negatives passed down by his family.

Although his own photography slowed down after several years of experimenting by shooting bands with a Canon Rebel T3, his interest was once reignited just prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, when his mother located her old Canon AE-1 Program, a 35mm single-lens reflex camera, and some old and expired film.

Using this camera, Peabody taught himself how to develop the film and also how to properly scan and color grade it digitally, which coincided with the time albums and boxes of old family photos and negatives began to come in his possession from his late grandmother’s house. Also, the memory of his grandmother shooting on a Polaroid Sun 600, which was released in the early 1980s, brings the full cycle back to his own photography today as he now uses that same camera for his own photography.

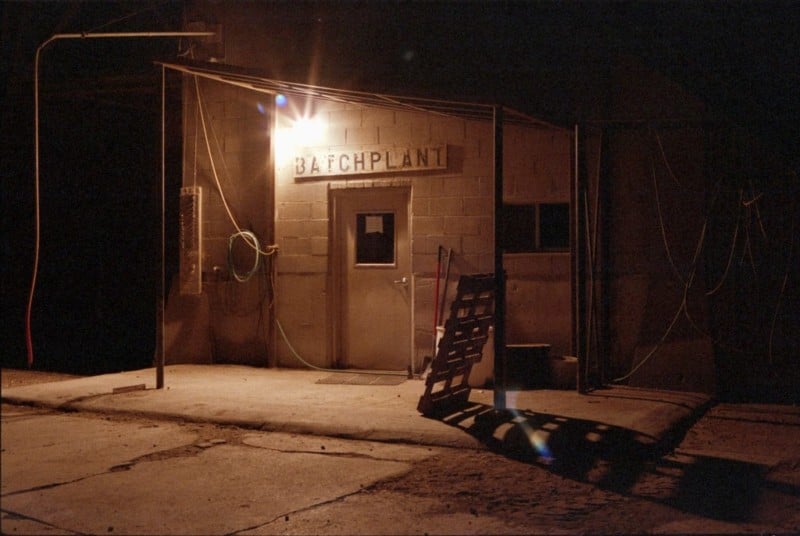

Peabody’s own photography revolves around photographing mundane or abandoned things, that may also be from a different generation, which is something he often comes across living in a small town.

Uncovering Decades of Past Lives

The discovered family collection of photographs and negatives dates back to the early 1900s and goes into the 1980s. Peabody recalls that “with the negatives, it seemed like a grand mystery because every negative I would mount would exceed my quality expectations upon the first preview scan,” particularly in regard to the photos taken in the 1950s and before, where framing and exposure were seemingly perfect and “provide a glimpse into the life of a generation.”

These photos have been accumulated and passed down from generations, and for the first time, Peabody is further preserving this rich collection of local social history by scanning and digitizing the photographs, giving them another life, and inviting the public to view them, too.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Although the photographer believes that these photos firstly belong to the family, he is also confident that “it is a sacred duty to preserve and share these stories,” because it also opens up the dialogue and helps connects the dots from person to person depicted in each of the photos.

The process of going through the photographs is time-consuming: although the images are somewhat organized, many of the negatives are still in the slips from the developer at the time or “stuffed into random containers of “See’s Famous Old Time Candies” and old Ziploc bags.

![]()

Even though photographs have been passed down by Peabody’s grandmother and also his mother, there are also collections of work that belong to different branches of the family, such as Peabody’s grandmother’s siblings and their lives, dating from 1940 to 1960. This takes Peabody’s work from merely scanning and digitizing to tracing connections between dates, locations, and people.

![]()

![]()

Some photographs have the year and the name of the person who had their film developed and the developer, for example, “B. Myers, AUG. 7 1936, Colorado Springs Drugstore,” which gives additional clues behind the story in these photos.

![]()

Peabody has learned quite a lot through this process, but it has also invited more questions than answers. His own knowledge in regard to the faces and places found in the photos was fairly limited, but he did know his grandparents met during World War 2, and that his grandmother lived in Hawaii during this time before moving to Colorado and then finally to Wyoming to retire.

“When you see family members, past and present, and uncover their stories you always reflect on your own life,” Peabody says. “It’s something that builds and expands your mind, much like traveling expands your knowledge and the same can be said about looking at unseen photos of mystery places and people.”

![]()

![]()

![]()

When it comes to recognizing his own immediate family in the photos, Peabody finds it easier to put names to the faces depicted, especially when the negatives are still in order in the sleeves they came in. For example, the photo series of Kelly’s Turkey Ranch, below, are easy to spot now that he has a location, familiar faces, and landscape to refer to.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Looking through the varied collection of photos, which have documented not just the family’s social life but also trips across the country, from Florida to Arkansas, and New Jersey, Peabody points out that he feels “it’s easy to get an idea in our heads that our elderly family members always enjoyed staying home, but to the contrary, I’ve found they were far better explorers than I am, and many times better photographers as well.”

“I’ve found quite a few photos mentioning a town called Calhan Colorado, which now seems to mostly be a ghost town,” Peabody says. “Photos of storefronts in the 1900s and schoolhouses are prevalent — many with handwriting detailing the identities of children in the lineup. Sometimes it feels like connecting the dots with string and pins to a missing person’s case or something.

“I’ve found that I have a long generation of adventurers, photographers, documentarians, ice skaters, servicemen, mothers, fathers, turkey farmers, car enthusiasts, travelers, heroes, and beautiful human beings.”

![]()

Peabody discovered a recurring character, referred to by the family as “Cousin Mike,” who served in the Vietnam War and was a photography enthusiast, developing and printing his own photographs in a darkroom. Some of the best images Peabody has come across, such as those of his mother ice-skating, have his name stamped on the back of the photos.

Peabody also found that Michael Conley, the full name of “Cousin Mike”, had courageously helped evacuate and rescue locals during the 1976 Big Thompson Flood, before tragically passing away. “Cousin Mike’s” courage and service, as well as his dedication to his photography and arts, is something Peabody found inspirational, and, by digitizing the images, the photographer can honor Conley’s life’s achievements and preserve the photographs he took.

Besides the people who can be identified by the living family members, Peabody came across many whose identities are unknown, as well as locations and license plates from areas that the photographer didn’t know he had a connection to. Some people were recurring subjects, while others appeared in the collection just once.

For example, the alligator photo, titled “Enemies”, below, as well as the unidentified man in a suit leaning against a pillar and the two young men with a cougar. Even though photos like these don’t reveal much about the connections to the family history, it still is “a window in time.”

![]()

![]()

Peabody explains, “I would say about a third of the photos I can recognize someone, a third is just landscape and people, and the remaining third is a mystery.”

Currently, the photographer intends to share the experience of these digitized vintage photographs, and the glimpse of the past they provide, with others. It has been and continues to be a lengthy task, as his family has gone to great lengths to try and organize the images and identify the subjects, and Peabody feels that it’s his duty to carry on, share, and preserve these memories.

He believes it is important to “open dialogue and show others that life is a flash, and the things that we do day-to-day might end up as a moment in time, captured as a negative in a dusty box.”

The Scanning and Digitizing Process

Peabody often invites viewers to join his live streams on Twitch, where he spends time scanning and digitizing the photographs at home. Because the process is time-consuming, Peabody found it to be a good medium for his workflow because while he is working on revealing long-lost images in real-time, having the audience join in makes it feel like “doing it with a friend,” who can provide both critique and praise.

As of now, the process of digitizing is fairly simple and cost-effective, the photographer says. Generally, he goes through a pack of negatives at a time, picking out the ones that catch his attention, with approximately 5 to 10 chosen images which take him 2 to 4 hours to scan and digitize.

![]()

![]()

For 35mm film, he loads the negatives into an Epson 35mm holder, which is equipped with anti-Newton ring glass. Aside from fluid mounting, this seems the best method for the photographer.

He then loads the entire holder in his Epson V700 scanner. For most of the medium 6 x 4.5-centimeter (2.4 x 1.8 inches) negatives, he mounts them on a small piece of photo frame glass with the dull edge facing down and some rubber bumpers to lift the negative off the scanner bed. So far, the photographer has had good results with this method but in the future would like to obtain a medium format mount for his scanner.

![]()

![]()

To get the most range out of his negatives, like setting the scan parameters, Peabody has researched various ways of working, such as from YouTube tutorials, and practiced those through trial and error. So far, the Epson scan software does a good job, the photographer says.

When it comes to editing, he starts by cropping the frames within the preview scan, then adjusts the histogram for the full range. Once he sets the mid-tones, to bring out enough detail, he scans it. In addition, he enables Epson’s Digital ICE Technology, which, from Peabody’s understanding, uses infrared light to detect scratches, fingerprints, hairs, and so forth.

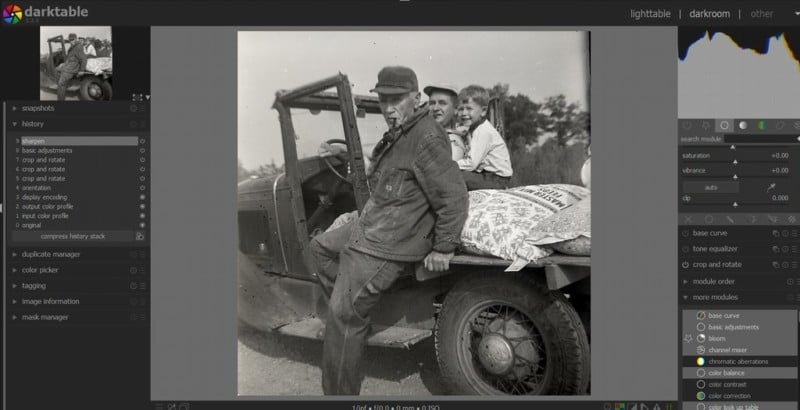

![]()

When the scan is complete, he uses Darktable, an open-source editor. Depending on what the image requires, he then crops and rotates the file, as well as works on basic adjustments.

During the color correction, the photographer tries to match the black and white to the original image, because some are more yellow while others are true black and white depending on if they are prints or not, while still giving himself room for any additional creative choices, such as slight hue alteration.

And, lastly, he corrects scars and scratches using Darktable’s retouch tool. Large distracting scratches are removed, while minor blemishes are left in. Peabody says that his process is relatively simple and his scanner, which was kindly donated to him by another photographer, who drove over a hundred miles to deliver it, does the majority of the hard work.

As with his own photography, Peabody currently doesn’t have a particular refined goal besides continuing his current process of scanning and digitizing but is open to any opportunities that may come his way, such as publishing his own zine or a photo book, dedicated to his family.

Having received support from the online community, his friends, and family, Peabody is willing to say yes to this journey wherever it takes him, the same way as Joel Meyerowitz said on a podcast, “every time something comes to me and I say ‘yes’ to it, I enter the next unfolding of being…. every time I press the button on the shutter, it’s a ‘yes’.”

A portion of Peabody’s scanned vintage images and his own photographs are available on his website and Instagram, and viewers can tune in on his Twitch streams to watch him scan and edit in real-time.

Image credits: All images used with the permission of Zachary Ian Peabody.

Author: Anete Lusina

Source: Petapixel