![]()

The Leica Freedom Train was not a physical coal or steam engine, but the monumental effort of the Leitz family. This is how they and the Leica camera company saved hundreds of Jews from persecution at the hands of the Nazis.

As the Second World War entered its final year, “The Song of the War Correspondents” was released in the Soviet Union. It was a triumphant, rousing, deeply nationalist anthem to the journalists who had covered the war. Perhaps it would be considered surprising, then, that in the first verse, a line praised a potent tool from a well-known German company.

With a Leica and a notebook, or even with a machine gun

Through the fire and cold we passed

The line is revealing on multiple levels. Even amid a global conflict in which borders were of the utmost imperative, captains of industry were using far different maps than captains of battalions. Of equal note is the simple equation of the lens with the firearm. Millions were dead and buried, their bodies pierced with metal and charred with flame, but the power of the captured image remained on equal footing to any armament. One name stood above all: Leica, produced by the Leitz Camera company.

Leitz Camera had been founded in 1869 by Ernst Leitz in Wetzlar, Germany, and had found swift success in a market desperate for microscopes and small optical elements. By the turn of the century, the production of optical devices had so aggressively expanded that the company built the first skyscrapers in the city.

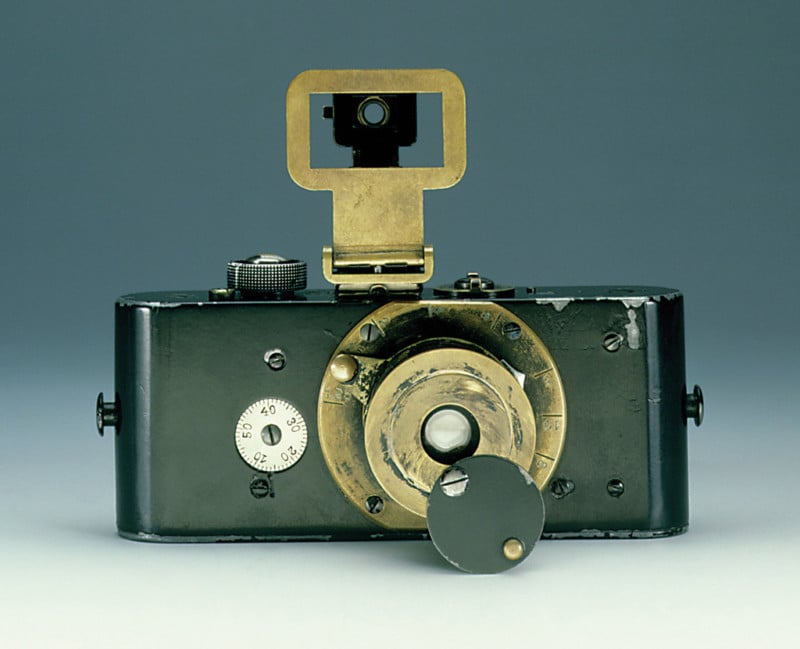

The dominance we associate with the company today, however, began when Oskar Barnack completed the world’s first practical 35mm camera — dubbed the Ur-Leica — in March of 1914. The goal of the Ur-Leica was to be as small and portable as possible, capturing a 24x36mm frame, by utilizing a smaller negative that, up to that point, had been used only for filmmaking. Movie cameras transported the film vertically which resulted in 18x24mm frames but by running the same film stock through the camera horizontally, a larger 24x36mm negative could be achieved.

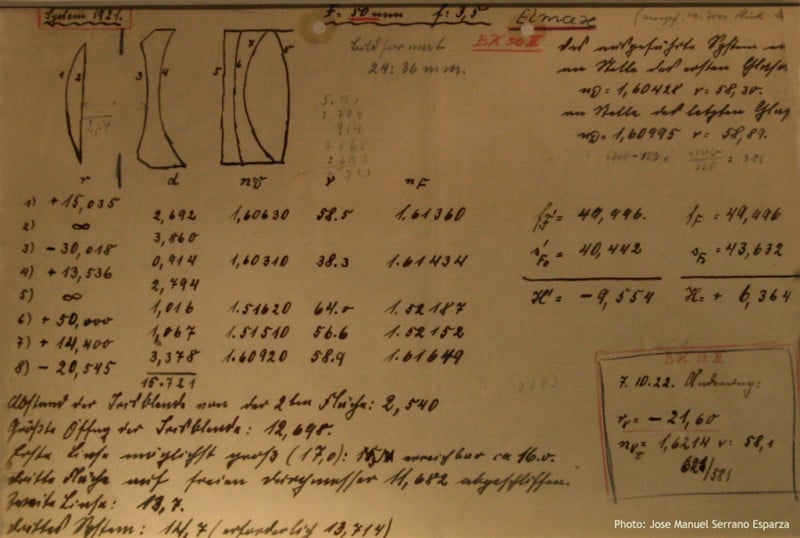

For such a camera to be functional, however, it required lenses of the highest quality, capable of resolving as much detail as possible for the negative. Physicist and Professor Max Berek was brought in to work with Barnack. Berek was a truly impressive innovator in the world of optics and a rather accomplished photographer in his own right. It was his considerable intellect that led to the invention of the lens that made the Leica truly work: a collapsible 50mm f/3.5 Leitz Anastigmat lens, which Berek based on the Cooke triplet design, with five elements in three groups.

To consistently produce and manufacture such refined lenses necessitated a stable, skilled team of laborers and technicians. This was no problem for Leitz Camera. Ernst had founded the company on a bedrock of progressive, pro-worker policies such as paid sick leave, employer-provided health insurance, and pensions, all of which were a bit of a rarity in the early 20th century, even in Europe. When Leitz passed the business onto his son, Ernst Leitz II, these policies — and the ethos that animated them — stayed firmly in place.

Unfortunately for the heir, he had taken the reins at a moment when every progressive Protestant value his father had instilled in him would be tested well beyond any normal breaking point. The Nazi Party was on the rise in Germany.

Leitz was no fool, and his understanding of politics was at least equaled his knowledge of the camera business. The same year Hitler came to power, Leitz ran for office as a candidate for the Deutsche Democratic Party, a far more left-wing organization keenly focused on maintaining a democratic, republican form of government in Germany. He not only saw the threat Hitler and his nationalist movement posed, but he also attempted to confront it in the marketplace of ideas.

It did little good. Hitler’s ascent was swift, aggressive, and assured. The Jewish people of Germany were acutely aware of what this meant. So was Leitz.

From its inception, the Leitz Camera Company had employed several Jewish laborers and technicians. Now, with Hitler as Chancellor, these workers, and their families, were panicked. Quietly and slowly, Leitz took the only action he could to protect them. One by one, bit by bit, he began arranging transfers for his Jewish employees to his offices abroad: France, Britain, Hong Kong, and America. The goal was simply to get them clear of Germany and the immediate, escalating threat. Leitz’s efforts extended beyond those who were already under his purview, going so far as to “hire” Jewish friends with the sole aim of getting them out of the country.

But just as surely as Leitz’s eye was on his new government, that government’s eye was on him, and on Leica. The reasons for the Nazi government’s obsession with Leica are as obvious as they are numerous. From a sheer nationalist branding perspective, an established German company of such high global repute, considered among the best in the world for its construction and skill, was a powerful marketing tool. That this impressive German company produced cameras that could be distributed and used in the furtherance of propaganda only made it more valuable. Finally, for a military keen on violent expansion of the homeland, securing production for the optical elements of powerful new rockets was a tactical necessity.

Shortly after Hitler took power, his Minister of Propaganda, Joseph Goebbels, ordered Leica cameras be used by his Propaganda Troops to capture striking images of the glory of Aryan life. The advancement made by Leica’s 35mm camera — the extreme portability and ability to capture both subjects and surrounding in a wide frame — was now used to indoctrinate the populace to the Nazi vision for Germany. The clarity afforded by the lenses so painstakingly developed by Berek was now being used to give detail to a lie that sought to destroy his nation.

As the grip of the Reich tightened, so too did the demands placed upon Leitz and Leitz Camera. Like Leitz, Berek was a Reichsbanner — a member of the alliance of those who sought to defend parliamentary democracy from the rise of fascism. While the Reichsbanners were formally disbanded upon Hitler’s ascent, the sentiment only hardened in Berek’s heart. The idea of participating in the Nazi regime in any way, shape, or form was repugnant to him. He refused to be a part of any work that would benefit the government and resigned from his position with Leitz Camera. His honorary title of professor was stripped by the Nazi regime.

In the fall of 1938, Hitler’s Storm Troopers and leaders from the Nazi party organized and carried out what was meant to appear as a spontaneous and sudden outburst of woeful street violence. Dubbed “Kristallnacht,” or “the night of broken glass,” Jewish communities were terrorized; their homes, synagogues, and businesses destroyed, their windows shattered. It was all pretext. As the pogrom spread, the Secret State Police and the Gestapo arrested tens of thousands of Jewish men and immediately transferred them to concentration camps. Immediately, the Nazi government blamed the Jews themselves for the pogroms and announced sweeping new sanctions on the Jewish community, stealing millions in their wealth. The sanctions were followed by dozens of laws and decrees designed to further strip the rights of Jews in Germany, barring them from most forms of employment, expelling them from schools, recalling their drivers’ licenses while restricting them from public transit, and banning them from most public entertainments.

In the years before Kristallnacht, Leitz had put in transfers for dozens upon dozens of “workers”. No sooner than Hitler had taken power had Leitz been inundated with calls from friends requesting assistance. Now, after Kristallnacht, these were calls begging quite literally for salvation. In the face of this vile Nazi acceleration, Leitz had no choice but to hasten his humanitarian efforts. The Leica Freedom Train was now at full speed.

While the exact number of lives Ernst Leitz II saved will never be tabulated, there are estimates that place the figure in the range of at least a few hundred. But his goodwill extended far beyond acting as a simple ferryman. Many of those aboard the Leica Freedom Train were destitute and facing an uncertain new life, perhaps permanently, in a foreign land. They needed not only passage but safe landing.

In New York City, German “employees” would disembark from the ocean liner Bremen and immediately report to Leitz’s Manhattan office. There, each new arrival was provided a brand-new Leica camera and paid a small stipend, despite possessing no real skills or legitimate value to the company, until they were able to sustain themselves. The message was clear: You are not forgotten. You are cared for.

It would be a romantic notion to consider the gift of the Leica through some pleasing metaphor about the power of photography, seeing a new world through a new eye or something to this effect. The reality, however, is that for many of these refugees, the Leica was meant as an insurance policy — an item to be bartered for enough scratch to get by a little while longer. There is very little romance about escaping your homeland due to a genocidal government bent on the destruction of your people.

Nowhere is the somber reality of Leitz’s efforts clearer than the life of 21-year-old photographer Kurt Rosenberg. Kurt had been a long-time Leica user as his father got him a four-year internship with the company when Kurt was just 16 years old. In 1938, he was brought to the United States as a Leitz employee. No one had to give Kurt a camera, he already had his own. He did, however, bring with him a typewriter. On it, he wrote numerous letters to the family left behind. He offered them hope, optimism, and detailed instructions on visa applications.

It little mattered. His mother perished in 1939. Later that year, his younger twin siblings managed to escape to the United States, only for one, Kurt’s brother Gert, to commit suicide months later. Kurt continued writing to his father, but it was no use. He died in the Lotz ghetto in 1942.

In 1943, Kurt joined the United States Army, no doubt compelled to do everything in his power to prevent the tragedy he and so many others had experienced from spreading. He was not even an American citizen at the time but was scheduled to receive his certificate of naturalization, a proud moment. He was killed in action before it arrived. Today, Kurt’s typewriter resides at the Holocaust Center for Humanity.

In 1939, Germany officially closed its borders, and the Leica Freedom Train was stopped. Still, Leitz and his camera company never stopped fighting from within. On multiple occasions, members of the company, or of Leitz’s family itself, were caught in the act of aiding Jews. Alfred Turk, sales manager for the company, was arrested for trying to help a Jew escape capture. Leitz paid a significant bribe to secure Turk’s release. It would not be the last time such arrangements would need to be made.

The Nazis were quite aware of Leitz’s activities, but the value of the company shielded Leitz from the worst of repercussions. In addition to its previously mentioned value to the Reich, Leitz Camera brought in massive amounts of foreign currency, which the Nazis could then use to fuel their war machine. By allowing Leitz to continue as a global company, even providing work for the opposing United States military, Germany surmised its own influx of capital exceeded the benefit gained from its adversaries. So Leitz, if he was discrete and made no real waves, faced no judgment. Leitz even went so far as to join the Nazi party in 1942 in order to maintain the tenuous arrangement.

This fragile, unspoken agreement was put to the test when Elsie Kühn-Leitz, Ernst’s own daughter, was captured by the Gestapo and imprisoned for attempting to help a Jewish woman flee into Switzerland. Elsie spent months locked away, suffering consistently harsh treatment as she was questioned and mistreated by the Nazis. Elsie was a mother, separated from her two young children, threatened by the most powerful evil in modern history, and refused to break. Finally, after considerable bribes and anguish, Ernst was able to have her freed.

Elsie refused to be cowed, and by 1943 found herself fighting the Gestapo once more. By this point, the war effort was underway. Slave labor was now the norm in many factories in Germany as a means of feeding the beast. Leitz Camera, once a bastion of progressive employment that would outstrip in virtue many American companies to this day, saw its floors filled with Ukrainian women held captive against their will, working for nothing more than the right to continue breathing. Elsie was disgusted. Without fear for her own safety, with full knowledge of the harsh consequences that could await her, she aggressively and vocally pressed for improved working conditions for the women. Her advocacy placed her once more under suspicion.

Finally, in 1945, the first American troops made their way into Wetzlar, Germany. The city had faced considerable bombing in the run-up to their arrival, but, thankfully, the majority of the Leitz Camera company was unharmed. Finally, Germany would be free of Hitler.

The story of the Leica Freedom Train has, by now, been told over a hundred times on a hundred different photography sites. We have even, to a lesser degree, covered it in the past here at PetaPixel. It may be told so frequently at this point that perhaps, for avid history or photography enthusiasts, it is considered old hat. But it is worth remembering that for decades upon decades after the Second World War, this story was entirely unknown. It is only relatively recently that the tale has received the attention it warrants mainly because the Leitz family saw no remarkable honor in their actions, and sought no gratitude or acclaim for what they had done.

With the same lack of hesitation Ernst Leitz displayed in deciding to pay his workers a livable wage, to offer them healthcare and time off when they were ill, to guarantee their basic rights as people, Ernst II and his daughter Elsie had decided to save human beings from a racist, ethno-nationalist movement bent on blaming, isolating, and eventually murdering them. These were uncomplicated ethical questions for the Leitz family. People deserve a good paycheck, people deserve healthcare, people deserve the right to life, and the people positioned to provide these things should simply commit to providing them.

To this day, the Leitz Camera Company — now called Leica Camera AG after its historic trade name — continues to offer much higher wages and benefits to those in their employ than most others within the same market. For the founders of the company, doing right was simply doing right; no fuss about it. That doing right got more difficult or personally costly meant nothing. What a world it could be if more modern companies had the simple courage and unshowy conviction of Ernst Leitz and his family.

Author: Matt Williams

Source: Petapixel