![]()

Ten years ago, I began making a series of images using a nylon bodystocking. The stretchy fabric created a dreamy space around the bodies of the models when they pushed out against it from inside.

We played many variations; one model in the cocoon, two models, smearing body paint or mud on the fabric to create texture, tearing the fabric so parts of the body were exposed. I called the project Cocoon and worked on it for about four years.

Note: This article contains a bit of artistic nudity.

Throughout the time that I was creating the images, I thought of them as an exploration of the body, the space around the body, and the sculptural forms of that space. I was interested in the formal aspects of the images. The series resulted in a solo show and was published in both print and online publications. I loved the images I made in the Cocoon project but other ideas called and I turned my camera to other things. The last time I showed the Cocoon images publicly was perhaps five years ago.

My images of models in the stretchy fabric might have remained stored safely on my hard drive had it not been for an inquiry from the photo editor of a German fashion magazine that arrived in my inbox late last year. She found the Cocoon images online and wanted to use three of them to accompany an article on stress.

As I went back through my files to select images for the magazine to consider, I found myself reacting differently to the Cocoon photographs. We were eight months into the COVID pandemic and the Cocoon images took on new meaning in that context. As I struggled with the physical constraints and emotional tension of stay-at-home orders and social distancing, the models straining against the body stocking seemed to represent what I and many others were experiencing. The image at the top of the page, for instance, had seemed a bit too dramatic at the time we made it. Now, I saw in it the desperation that so many people feel as normal day-to-day activities are curtailed and social connections are cut off. The context changed, and with it what I saw in the photos changed, too.

I sent the image files off to the German magazine but I found myself drawn back to the Cocoon images. This one reminded me that even when we find ourselves quarantined with another person, there is still a sense of contraction and entrapment. We need our loved ones and our friends but we also need our solitude.

When I saw this one again, I knew that there are also moments of peace and beauty in the midst of all that we are wrestling with.

I thought immediately of the words of an old folk song when I saw this image. It was in the midst of political conflict in the US and people from both sides were taking to the streets. Peter, Paul and Mary sang it, “there’s anger in the land.”

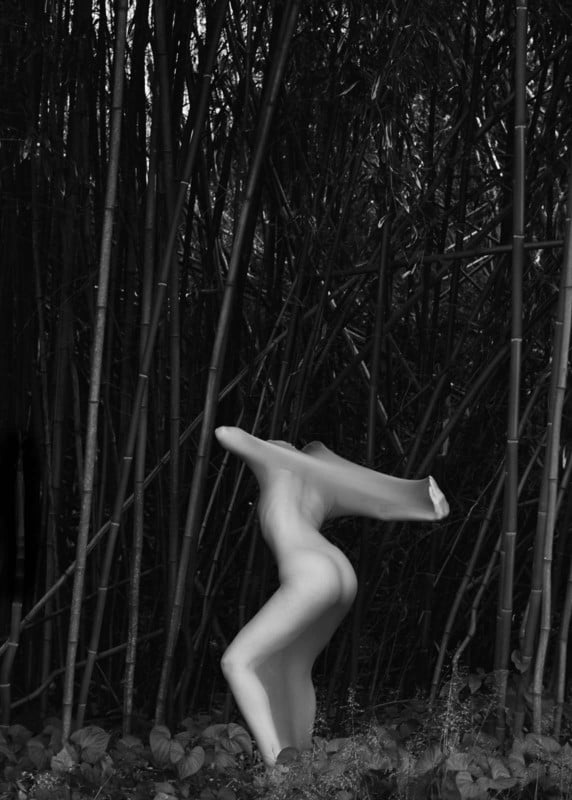

Even when outdoors, we are still caught — reticent to approach other people, seeking solitary pursuits, out of the house yet not really free.

And then there are days when it seems we will somehow find our way out of all that has entrapped us and, like a true cocoon, emerge with new wings.

Photographs live in a context, and that context determines, in part, how we understand them. My formal exploration of the body became a representation of the emotional experience of quarantine when I looked at the photographs from a different vantage point. While photographs capture and preserve moments in time, they don’t become static. They live along with us, open to new understandings.

As we change, and our circumstances change, what we see in photographs changes, too.

About the author: E. E. McCollum is a photographer and writer living in the American Southwest. The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author. McCollum is also the Editor-at-large of Shadow and Light Magazine. You can find more of McCollum’s work on his website. This article was also published here.

Author: E. E. McCollum

Source: Petapixel