![]()

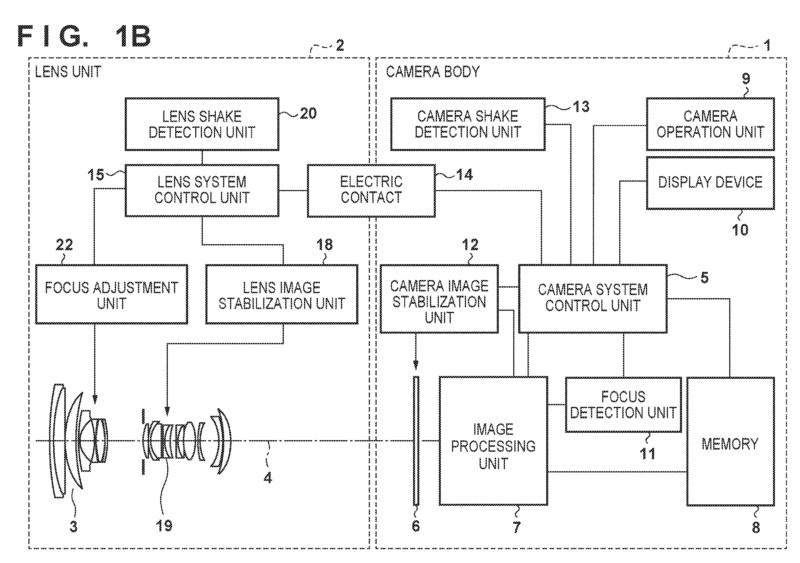

Canon has applied for a patent that would allow a camera to use its in-body-image-stabilization (IBIS) to approximate the effects of an anti-aliasing filter. The idea is similar to how sensor-shift multi-shot works, but in reverse.

The application — which was found by Northlight Images and shared by Canon Rumors — notes that Canon is proposing a way for the sensor to shift during image capture in such a way that it approximates how an anti-aliasing filter works.

As Northlight Images writes, the idea “uses fine movement of the sensor stabilization system to perform one of the jobs of the anti-alias filter for the AF system and address problems of sampling and spatial aliasing. A version for DPAF and contrast AF is discussed… The fine control of sensor positioning is also part of a multishot super-resolution solution, where a traditional AA filter might also get in the way.”

If this idea sounds familiar, it is because it is a technology that Pentax has been using in its cameras for several years, including the most recently announced K-3 Mark III. The video below shows how the technology works:

Basically, unlike sensor-shift high-resolution photo modes that use a camera’s image stabilizer to capture more data and compile a high-resolution image in-camera, this feature would quite literally do the opposite and move the sensor to effectively blur the image slightly and give the appearance of an anti-aliasing filter.

As Ricoh explains:

Based on original ideas and innovative technology, Pentax has developed the world’s first AA filter simulator, which reproduces the effects created by an optical AA filter. By applying microscopic vibrations to the CMOS sensor during exposure, the K-3 minimizes false color and moiré. You have a choice of three settings to obtain the desired effect: “TYPE 1” to attain the optimum balance between image resolution and moiré; “TYPE 2” to prioritize moiré compensation, and “OFF” to prioritize image resolution. Thanks to this innovative feature, the K-3 offers the benefits of two completely different cameras — the high-resolution images assured by an AA-filter-free model, and minimized false color and moiré assured by an AA-filter-equipped one. You can switch the AA filter effect on and off as you wish.

This feature is not magic, however, and has limitations. Using a camera’s image stabilizer on a pixel-level like this while shooting has some tradeoffs. For example, Ricoh states that the AA-filter effect is “more evident” when a shutter speed of 1/1000 second or slower is used, which dramatically reduces the feature’s usability in anything other than brightly lit conditions.

For those unfamiliar, anti-aliasing filters — also known as optical low-pass filters — were designed to deal with a situation where the spatial frequency of what a digital camera is trying to photograph was smaller than the pixel spacing on a sensor. This is most commonly found when taking photos and videos of tight patterns on fabrics or wide-angle shots of buildings where windows are particularly close together. The resulting visual discrepancy is referred to as moire, which is a French term that means “watered textile” and accurately describes what the visual effect looks like: wavy water. An optical low-pass filter was placed in front of the image sensor in a majority of digital cameras up until the last several years and would make the moire less noticeable or have it disappear entirely. The side effect, however, was a drop in perceived sharpness.

Pentax and now Canon are not the only companies that have tried to come up with ways to give photographers a way to turn the idea of an anti-aliasing filter on and off. Sony pioneered a digital low-pass filter technology into its RX1R Mark II camera.

“Splitting of incident light flux is controlled by varying voltage to the liquid crystal between low-pass filter one and low-pass filter two in order to activate, deactivate, and modify low-pass filter effect. LPF bracketing simplifies comparison of LPF effects,” the company writes.

![]()

Because it was electrically controlled and responded nearly instantaneously, photographers could configure how it would work and even apply an “auto” mode to it. It’s unclear as to why this feature is only in a fixed lens camera and not found in any of Sony’s Alpha cameras, and that may be related to the fixed-lens nature of the RX1R Mark II.

Another reason it might not be in other cameras is the need for an optical low-pass filter is disappearing.

It used to be that anti-aliasing filters were quite common, but in the most recent releases by most manufacturers, it is not a feature that even makes it onto the public-facing specifications sheet. This is because as cameras grow in resolution and have smaller and smaller pixels, the incidence of moire even without an anti-aliasing filter has fallen dramatically. Basically, it has become less likely that the subjects photographers are taking pictures of have a spatial frequency that is smaller than the distance between pixels on modern sensors.

As a result, some may find it a bit odd to see Canon attempt to patent a technology to address a problem that has been shrinking in importance over the last few years. Additionally, since Pentax clearly already uses a similar technology, Canon’s patent has to obviously do something different in order to get around the fact a competitor has been using a similar idea in the market for almost a decade. You can read the full patent application here.

Author: Jaron Schneider

Source: Petapixel