When Alfred Eisenstaedt, one of Life‘s original four staff photographers, first shot Sophia Loren for the magazine, she was already on the cusp of international stardom.

Born Sofia Costanza Brigida Villani Scicolone in 1934, the actress had risen from working as an extra to leading lady. By 1961, she was establishing herself as a glamorous icon and a serious actress in equal measure, epitomizing the height of Italian glamour.

Yet what began as a routine magazine assignment evolved into something far more valuable: an 18-year photographic relationship that produced nearly 200 images, most of which never saw print.

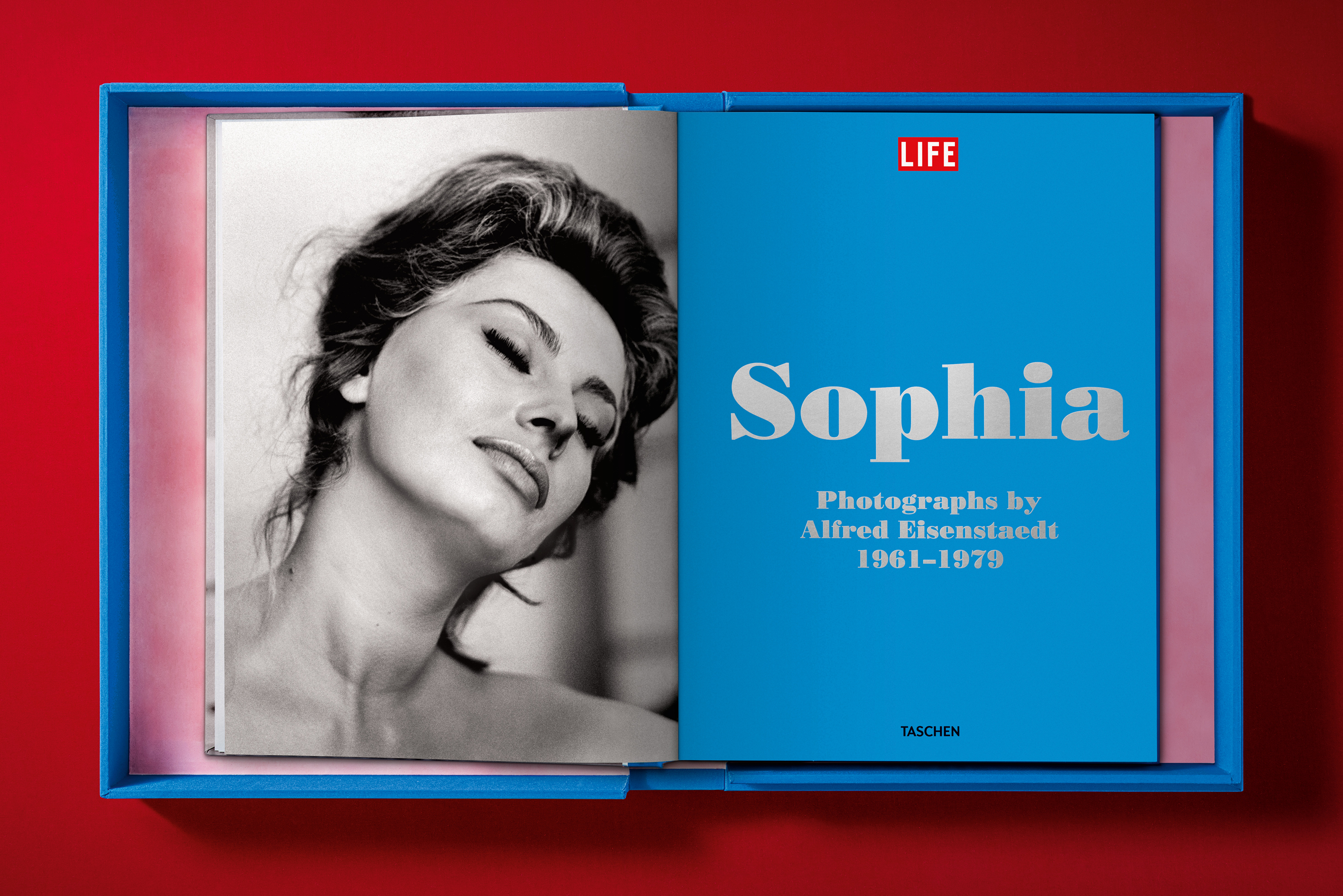

That’s the revelation at the heart of Taschen’s new collector’s edition, Sophia by Eisenstaedt, published this month.

While “Eisie” shot 80 covers for Life during his 50-year career with the magazine, the vast majority of his Loren work remained in the archives – and has now been scanned from original negatives. For photographers operating in today’s publish-everything-immediately culture, the restraint is almost unfathomable.

Shooting and smiling

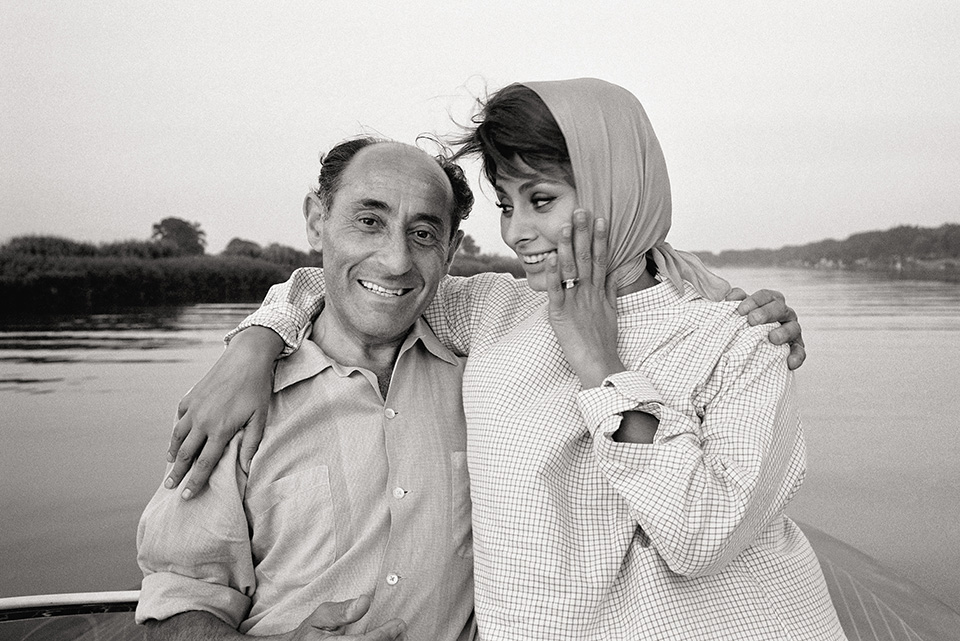

The images span 1961 to 1979, capturing Loren on film sets alongside Marcello Mastroianni, Marlon Brando and Charlie Chaplin; in her humble family home near Naples, providing a grounded contrast to her later life; at her majestic Roman villa with husband and producer Carlo Ponti; and in candid moments raising her sons in Paris.

Eisenstaedt, already four decades into his legendary career when they met, became what Loren called her shadow. “He never tried to interfere in my life,” Loren recalled. “He just kept on shooting and smiling and was happy just to be with me like I was to be with him.”

That relationship speaks volumes. Eisenstaedt, who revolutionized photojournalism with his iconic 1945 Times Square V-J Day image, understood something essential about portraiture: the best images emerge not from aggressive pursuit but from patient presence.

He didn’t bark orders or manufacture moments. According to Hollywood historian Justin Humphreys, the 1961 shoots saw Loren “more casual and her interactions with Eisenstaedt more spontaneous” compared to later, more formal sessions, reflecting “the stately surroundings and Loren’s elevation from a famous actress to a global phenomenon”.

This unique rapport enabled Eisenstaedt to witness Loren’s private world as she transitioned into motherhood in 1969 and raised her sons, Carlo Jr and Edoardo, in Paris. Their connection was built on a unique camaraderie that went beyond a standard professional assignment, with Eisenstaedt capturing her not just as a goddess but as a relatable everywoman.

For contemporary photographers drowning in digital abundance – where a single fashion shoot might yield thousands of frames instantly uploaded to cloud storage – the editing discipline of the Life era offers a counterpoint.

Each of Eisenstaedt’s 2,500 assignments for the magazine was ruthlessly curated. Images that made it to print were the survivors of exhaustive selection processes. The fact that so many strong images never ran says something profound about editorial standards then versus now.

The book also documents a working method increasingly rare in celebrity photography today: repeated access over years, rather than minutes. Eisenstaedt photographed Loren in 1961, 1964, 1966, 1969, 1976 and 1979. Each session built on the previous one’s trust.

By the final New York shoot in 1979, when Loren was promoting her memoir, the rapport was complete. No publicist hovering, no 15-minute slot with hair and makeup people swarming between frames.

Age of authenticity

This collector’s edition (numbers 201-1,200, signed by Loren) arrives at an interesting moment.

In an age when celebrity images are increasingly stage-managed Instagram posts, Eisenstaedt’s work reminds us what portrait intimacy looks like. Above all, it required time, consistency and a photographer secure enough in his craft that he could recede into the background.

The images show Loren as she was: radiant in costume, introspective between takes, domestic in her gardens, maternal with her children. Not because Eisenstaedt manufactured these moments, but because over 18 years he earned the right to simply be there when they happened.

For photographers today, that’s the real lesson; one that has nothing to do with gear or technique and everything to do with the relationship between person and lens.

Sophia by Eisenstaedt is published by Taschen, priced $1,000 / £850. This 268-page, limited-edition hardcover, presented in a clamshell box, features an essay by Professor Stephen Gundle and captions by Hollywood historian Justin Humphreys.

Author: Tom May

Source: DigitalCameraWorld

Reviewed By: Editorial Team